Did you know that the average school-aged student learns between 3000 to 5000 words per year?

That means they learn eight to 12 words per day (Biemiller & Boote, 2006).

Most children are like little sponges soaking up new information.

Unfortunately this isn’t the case for students with language disorders who have limited word knowledge.

Students with weak vocabulary skills only learn 300 to 900 new words per year, or one to three per day (Cain, 2007).

This means our students with language delays are getting further and further behind.

It’s an SLP’s job to build our students’ vocabulary, but how on earth can we make up this difference with the limited time we have?

The quick and dirty answer: We teach them the RIGHT words.

Tier 2 Words: Is it enough for students with language disorders?

We don’t have time to teach students every single word they’ll need to know.

Direct therapy time never seems long enough, so when we choose words to target we need to make it count.

You’ve probably heard the buzz about Tier 2 words based on the work of Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan in their book, Bringing Words to Life (2002).

The challenge for us as SLPs is that Beck at el. designed this framework for teachers who have daily Language Arts periods. We don’t have that luxury.

Beck et al. also created the framework for the general education curriculum. It offers an amazing way to differentiate instruction, but that’s not enough for our students with language disorders.

Our students need something different. Tier 2 words are a priority, but we don’t have time to target ALL the Tier 2 words teachers cover in the curriculum.

In other words, we need to prioritize from the words we’ve already prioritized.

How can SLPs prioritize Tier 2 Words?

The key to selecting appropriate vocabulary is understanding why Tier 2 words were selected in the first place.

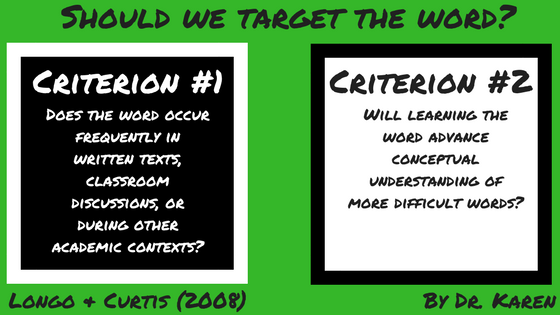

We can do this by asking ourselves two key questions outlined by Longo and Curtis (2008):

Criterion 1: Does the word occur frequently in written texts, classroom discussions, or during other academic contexts?

We want to make sure the words we teach will have a global impact.

This means we should work on words that students will use across multiple subjects, units, and even grade levels.

This also means that we may focus less on words that may be difficult for students, but aren’t used often.

This may include words that are specific to a specific content area or unit that students won’t be required to use once that unit is completed.

Criterion 2: Will learning the word advance conceptual understanding of more difficult words?

Some words are used often but we don’t need to address them if they are easy for our students. This would include words that occur often in conversation.

Teaching everyday “conversational words” is less of a priority words if students have adequate exposures and opportunities to use them during day-to-day conversations.

On the other hand, “text” language or “academic” terms don’t occur often in conversation, which means students have fewer opportunities for exposure and practice.

Yet, these terms occur frequently across academic settings, and students need to understand them to perform academic tasks (e.g., taking assessments, participating in classroom discussions and activities).

For students with language disorders, this is often the sticking point. If they don’t have an understanding of frequently occurring “academic” vocabulary, they get lost in the shuffle.

So lost, in fact, that they are less likely to learn more difficult language specific to content areas.

Because of this, learning “academic words” can bridge the gap, and allow students to function more effectively across academic settings. This can help students to grasp on to more challenging words and concepts.

Think of it as teaching your students to fish, rather than giving them the fish.

Our goal as clinicians is to give our students the skills they need to learn more effectively once they leave the therapy room.

Let’s look at some specific examples. Look at the words compare and contrast.

Students are often asked to compare or contrast complex concepts on tests and assignments. If they don’t know what these words mean, they won’t know how to answer.

There are many other similar terms, such as define, explain, or analyze that students will need to know to complete academic tasks across many subjects.

By addressing these types of, we are helping students learn words that will need to know to answer questions or have discussions about more difficult concepts.

Words like this would meet Longo and Curtis’s second criterion.

How the “three tiers” work for most students

I’m a huge fan of Beck et al.’s framework, and by no means am I dismissing it. I’m simply suggesting that SLPs view it with a different lens, because our role is distinctly different than the teacher’s.

What I’m suggesting is that SLPs use Beck et al.’s framework as a starting point for prioritizing vocabulary.

Then, I recommend that they revisit Longo and Curtis’s questions to narrow it down even further and individualize.

Before I can explain what I mean, let’s look at how the three tiers might look for typically developing students.

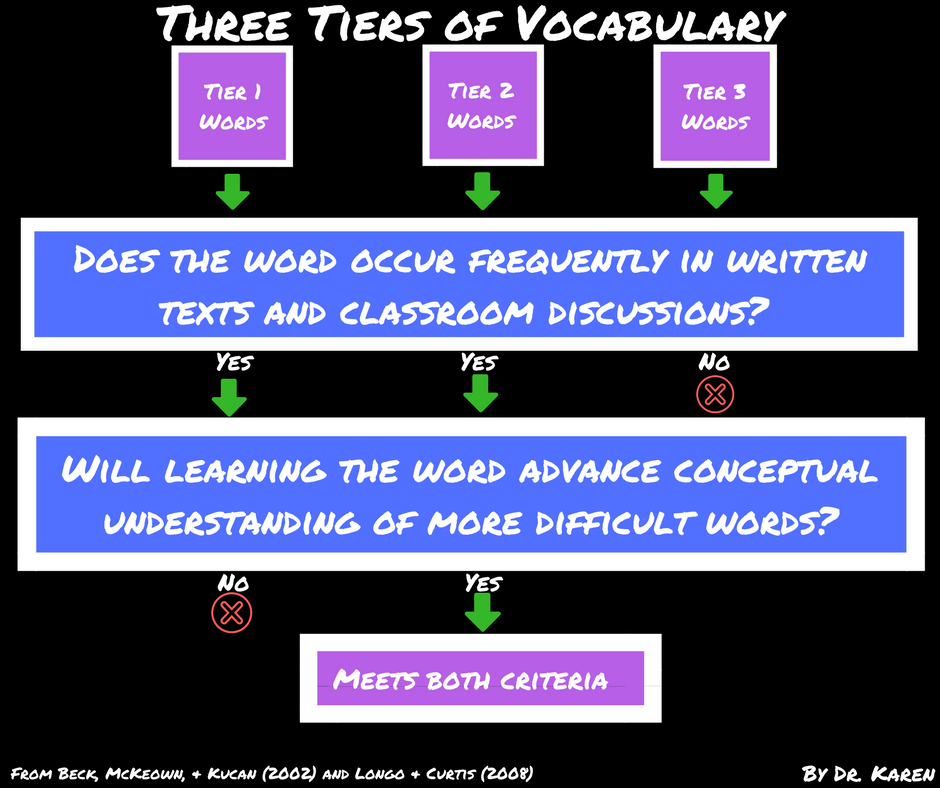

Tier 1 Words: Low priority

“Tier 1” words are those that are familiar to most students and occur often in conversation.

According to Beck et al., teaching Tier 1 words isn’t a high priority because the majority of children already know what they mean. For most students, teaching these words won’t have a significant impact on their ability to learn more difficult words.

This means that for the typical student, Tier 1 words meet Longo and Curtis’s first criterion (occur frequently), but not the second (will advance understanding of more difficult words).

Tier 2 Words: High priority

Students encounter “Tier 2” words frequently across academic settings. This means they meet Longo and Curtis’s first criterion (occur frequently). These words are more complex than Tier 1 words and often appear in written language across content areas.

Tier 2 words are difficult enough that learning them increases understanding of more complex concepts, so they also meet Longo and Curtis’s second criterion.

Tier 3 Words: Low priority

“Tier 3” words are specific to content areas (e.g. science, social studies), which means they don’t occur as often as Tier 2 Words.

While it’s appropriate for teachers to discuss them in the contexts of context of content areas, they don’t occur frequently enough to meet Longo and Curtis’ first criterion.

I’ve outlined the process, and how these two frameworks line up in this flowchart:

How the “three tiers” work for students with language disorders.

You can see from my explanation above, that Beck et al.’s three tiers follow Longo and Curtis’s criteria for most students.

It might work for a lot of students you see for language therapy, but we can’t make the assumption that it will work for all of them.

We know that general education instruction is not enough for our students with language disorders. That means that we need to add an extra step to the process to make it appropriate for therapy.

Step 1: Start with Tier 2 words.

Having a clear starting point will keep us efficient. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel when someone’s started the process for us.

The first thing you can do is identify the Tier 2 words students need to know in the general education curriculum. You can do this by talking to teachers or reviewing texts your students are reading. In this free video for SLPs, I explain how to do that and give some examples of high-quality vocabulary for your language therapy.

Step 2: Revisit Longo and Curtis’s criteria

Why are we doing this again? For several reasons.

First, we aren’t going to have enough time for all of the Tier 2 words in our limited therapy time. That means we can revisit Longo and Curtis’s two questions to narrow the Tier 2 word even further. As I said before, we prioritize what’s already been prioritized.

This will be the step you want to take for students with “mild” language disorders who may be able to function well in day-to-day casual situations, but struggle with rich academic vocabulary.

In many our our cases, we can gain the most ground in therapy if we focus on Tier 2 words.

The second reason we revisit the criteria is because some of our students may not be ready for Tier 2 words.

For a student with a language disorder, we may be able to say “yes” to both Longo and Curtis’s questions when we’re talking about Tier 1 words.

For example, many students struggle with basic temporal and spatial terms, such as before/after, under/over, or top/bottom.

What we’re doing is revisiting the theory behind the “three tiers”, because what’s a priority for one student may not be a priority for another.

This ability individualize is what makes SLPs different from teachers.

Teachers bring an important piece of the puzzle. They are the experts in curricular expectations.

You, as an SLP, bring the clinical judgement and ability to make it unique for those students who are struggling.

You’re there for those students who need something more, or something different.

Because when it comes to vocabulary intervention and language therapy, SLPs need to be well-equipped to answer some difficult questions.

There are the clinical questions we ask ourselves, like:

… “Should I even be teaching vocabulary words in therapy?”

… “How on earth can I make time to dig through all of those curricular materials to find vocabulary words?”

… “How do I know how many words I can cover each week?”

… “Is it even possible to get to all the words my students need to know with the limited time I have?”

… “How do I figure out if my clients truly “know” the words I’m teaching them?”

… “Will I ever be able to make a difference when my clients are so far behind?

… “How do I focus on teaching the right words that make a difference?”

And then there are the questions that come from other people we work with.

… “But you’re a speech therapist. What do you have to do with reading? I thought you just fixed the “r” sound.”

… “But this other after-school tutor is way cheaper. Why should I pay more for my child to come to private therapy with you?”

…“But the teachers are the ones who are supposed to be working on vocabulary. How is what you’re doing different?”

In order to be effective and truly serve your clients, you need answers to these questions.

In my signature program, Language Therapy Advance, I help clinicians find the answers to these types of questions, so they can leverage their expertise and gain more confidence in their clinical skills, and break through therapy plateaus (especially relating to spelling and grammar)…

I also go in to more details about how you can boost grammar, spelling, and literacy skills…as well as create high-impact language therapy systems.

I used to feel like I was banging my head against a concrete wall as I drilled the same old grammar flashcards over and over again. And I was clueless what to do about spelling.

But when I started truly studying how language works during my doctoral program, things all started to make sense.

In Language Therapy Advance, I aim to share those systems with SLPs like you, so you can make massive breakthroughs with your students, establish yourself as a trusted expert, and find more fulfillment in your career.

If you want to learn a tried-and-true system for remediating the root cause of processing issues, join the Language Therapy Advance waiting list to learn when course enrollment opens.

References:

Longo, A.M., & Curtis, M.E. (2008). Improving vocabulary knowledge of struggling readers. The NERA Journal, 44, 23-28.