One of the most common questions I get from clinicians who work with school-age kids is about scope and sequence of therapy.

“How do I make time to address all these skills my students need?”

“How can I help students generalize skills from one setting to another?”

“How can I help the other people on my team value and understand my specific discipline?”

I started off as an SLP, which means I was thinking about these questions within the context of the SLP’s role in language and literacy intervention.

But as I expanded to special education leadership and started looking at this in the context of the entire school team, I found that many other clinical disciplines and teachers from different content areas are all asking these same questions in some way.

There are endless debates about what is and isn’t evidence-based, what is developmentally appropriate and reasonable to expect from students, and how we should design programs and services.

Many of these questions are centered around the STUDENTS, and they should be to some extent.

But not at the expense of the adults.

Adequate Services versus Optimal Services

School therapists I’ve interacted with face moral dilemmas on a daily basis.

They’re legally mandated to provide services that are educationally relevant. The goal of therapy is NOT to optimize functioning, but rather to provide a “reasonable and appropriate” amount of intervention to ensure access to the curriculum.

This can be challenging, because many parents (and some outside therapists and medical professionals) don’t understand school eligibility guidelines.

This means school therapists and administrators are put in the difficult position of having to explain to families why their job isn’t to provide the “best” services, it’s to provide “appropriate” services.

This isn’t because they’re trying to be stingy; it’s because they’re working in a publicly funded system and there have to be clear guidelines about what is and isn’t covered.

Now, typically people don’t decide to work in the schools with the goal of providing services that are “reasonable, appropriate, and adequate”. They want to be life-changing, even if they’re not legally required to do it.

This is where things start to get confusing.

When we’re talking about cognitive development and prerequisite skills, how much is support reasonable to expect from people working in the schools?

Teachers, for example, need to have an in-depth grasp on scope and sequence of curriculum.

Therefore, it makes sense for teachers to spend a fair amount of time developing an in-depth understanding of curricular expectations and alignment.

But focusing on curriculum can result in criticism and claims that schools are being cookie-cutter and too focused on standards and testing (even though it would be complete chaos if we went too far in the other direction).

For the therapists who work in schools, they not only have to have competency in their clinical discipline and diagnostic procedures, but they ALSO need to establish an understanding of the curriculum to make sure their services are educationally relevant.

Because clinicians are not trained to be experts in K-12 scope and sequence to the extent that teachers are, this is a huge learning curve for therapists first entering the schools.

I remember how I felt each time I’d attend a seminar during my first few years in the schools; particularly the first time I attended my state conference.

After enduring a day of sessions outlining protocols I knew I’d never be able to deliver, I started to feel extremely inadequate.

Nothing is worse than being told by other professionals in the field that you’re missing key components of intervention, and going to work day after day questioning whether you’ll ever live up to those standards.

Is it the chicken or the egg? (e.g., language versus executive functioning)

One of the things that makes intervention particularly difficult for school-based professionals is determining what is the highest priority.

Since you can’t be “optimal” you have to be really clear on how you can make the most of the little time you do have.

One of the things people do to solve this problem is try to determine the “root cause” of issues students may be having.

Most disciplines have that ONE area that is much more difficult to treat than others. For SLPs, that’s often language therapy; especially if they’re working in the schools.

While protocols for other conditions have more prescriptive options; addressing a language issue is highly complex; especially as it pertains to reading and writing.

SLPs have a background in brain development. Cognition and language are interrelated, which expands their scope even further.

Part of the training SLPs get relates to adult neurology, and includes rehabilitation focused on cognitive functioning during daily activities. Therefore, it would also make sense for school SLPs to also support students with brain differences who present with executive dysfunction.

Now here’s where it gets even more confusing from both a clinical and a feasibility standpoint.

Language and executive functioning have a bidirectional relationship (Baron & Arbel, 2022; Larson, et al., 2019). This means that building language skills can impact executive functioning, and vice versa. I talk a lot about this in my conversation with speech-language pathologist Jill Fahy in episode 122 of De Facto Leaders.

A significant amount of executive functioning skills are required to comprehend language-based academic tasks like reading and writing.

Yet strategic thinking (which is part of executive functioning) requires a significant amount of internal dialogue; which is very difficult to engage in without adequate vocabulary or ability to use and understand complex syntax (Fahy, 2014).

Complex sentences are loaded with language that indicates cause and effect or temporal information; all which are essential for strategic planning. On top of that, many students continue to struggle with reading comprehension without direct work on foundational language skills; even if they’re taught comprehension strategies (Eberhardt, 2013; Scott, 2009; Scott & Koonce, 2014; Nippold, 2017).

One might make the argument then (which I often do), that these underlying language skills are necessary to developing strong executive functioning skills.

Okay then, it’s settled. SLPs should be focusing on their language therapy skills first, right?

Well, it’s not that simple.

Daily functional tasks, like packing a bag or managing your belongings, all require executive functioning skills. Regulating your emotions, noticing how you’re coming across, being able to evaluate your own behavior and performance, and noticing cues in the environment around you also require executive functioning skills.

In order to benefit from certain academic and language-based tasks, one needs to be able to self-regulate, inhibit, initiate, and persist through tasks. All of these skills fall under the umbrella of executive functioning and all of them affect much more than just language-based academic tasks.

So you could ALSO make the argument that focusing on executive functioning is a high priority.

In a perfect world a child who needs BOTH executive functioning therapy and language therapy would get them both. And in theory, it could be an SLP providing both of those interventions

If I could magically fix the school staffing shortages and huge caseloads, I’d say SLPs should make BOTH things a priority all at once.

But making that happen is a logistical nightmare; especially for clinicians who feel like they’re barely getting by.

So we have to get a bit more creative in how we solve this.

(Before I continue, it’s important to note that other professionals besides SLPs can also address executive functioning given they have the appropriate training. This includes psychologists, social workers, counselors, social workers, teachers, etc. Be aware that there are many “coaches” doing this kind of work who do not have legitimate professional licensure. What I’m outlining in this article is designed to help qualified professionals bolster their existing credentials and skills).

The “client-focused” questions

Usually when clinicians discuss ways to establish a therapy plan, they focus on what is evidence-based, what an appropriate developmental progression should look like, and methods for differential diagnosis.

Our job as clinicians (or teachers) is to support human beings, so OF COURSE we need to make what we do tailored to client/student needs.

All of these factors are important, valid, and I use many of them in my decision-making process when I come up with course curriculum and program features for my clinical training programs.

But quality research takes time and resources to conduct, meaning clinicians need to also layer their clinical expertise and experience into their decision-making process. Additionally, there are a number of developmental models and theories, which means theory to implementation leaves a lot open to interpretation.

Diagnostic procedures aren’t foolproof. Many times it’s difficult to get a complete picture of a client’s profile based on the time and resources we have available; partially due to time constraints and sometimes due to the nature of what we’re trying to assess.

When you start to get into discussions of the root cause, it gets even more complicated.

I think we SHOULD be thinking about these things. We shouldn’t dismiss them for the sheer reason that they’re challenging questions to answer.

But there comes a point of diminishing returns where you have to let go of the need to know you’ve picked the “right” path.

At some point, you have to pick a direction that has a reasonable amount of evidence to support it in the interest of moving forward, getting feedback, and adjusting along the way.

Many of the problems we’re facing in education aren’t because the teachers, therapists, and administrators don’t know what kids need to succeed. It isn’t a question of what the kids need.

It’s a question of what the adults need to make things happen.

That’s why I’m proposing a less conventional way to answer the, “What should I prioritize in therapy?” question.

The Product Management Approach

Since starting my business back in 2015, I’ve had the opportunity to learn more about how tech teams work.

When tech teams build and maintain a software application, there’s an entire team of people who keep it running and updated. Users can submit support requests, and adjacent departments within a company can also submit requests depending on whether the application is customer-facing, or whether it’s a tool for internal employees.

Teams can consist of a handful of technical professionals; web developers, user-experience designers, subject-matter experts, as well as product managers who manage the backlog of requests and distribute the work among the team.

This methodology is used across multiple industries; including the K-12 curriculum market, which I discussed with EdTech leader and former math teacher Meg Hearn in this conversation.

One of the biggest challenges in managing the backlog of requests on a particular product is estimating what projects are the highest priority.

As Meg shared in our conversation, determining what to prioritize is both an art and a science. Some things have to be taken care of right away or the application will break. Other things become a priority because there is a downstream impact; for example, another team will not be able to complete their work unless a certain project is completed.

Others may become a priority because of the immediate impact on the experience of a user. For example, if have an education product for kids and the school gets an influx of students who speak a different language and text needs to be translated, that could be an item on your backlog.

Maybe you have another customer that’s requesting accessibility features be added for students with visual impairments. You also have a button that’s not working and students don’t know how to navigate from one screen to another; creating a ton of extra work for teachers using it in their classrooms.

These things all sound pretty important, right? So how do we sequence this list of items?

Let’s say you want your product to be available in another language, but it’s a huge undertaking. The accessibility feature and issue with the button are smaller projects that you can complete more quickly, so you prioritize those first. This frees up resources for a bigger project, like the language translation.

The rationale is still about impact on the user, but it’s also about feasibility and the team needs.

You need to be thoughtful in your process, but if you spend too much time debating, you prevent the projects from happening in a reasonable length of time.

If you focus on too many things at once, your resources get stretched too thin and you compromise the integrity of the work.

Someone needs to make the difficult decision of tabling projects that have a solid rationale behind them in the interest of seeing the big picture.

Contrast this to what people expect from teachers, school therapists, and administrators.

People in education are often expected to make everything a priority all the time, without consideration of how they might be able to manage the backlog of projects.

They have to say “No” to people who need help in the interest of saying “Yes” to others. They have to see the faces of the people their decisions are impacting.

While there is an understanding that prioritization is part of the methodology when you’re thinking about this from a product management perspective within an enterprise, it’s viewed with much more skepticism when it’s done in education.

When teachers, school therapists, and school administrators have to say “No” they’re accused of focusing too much on test scores, being obsessed with funding, making it all about the grades and the standards, or not being inclusive and individualized enough for students.

These concerns come with good intentions because they’re focused on STUDENTS.

But how often do we ask, “What is the best scope and sequence for supporting the adults?”

The “Adult-focused” questions

For teachers in core and content areas, they first and foremost need the foundational skills and tools to deliver the curriculum.

They also need to bolster that knowledge by learning skills that help them differentiate their instruction, increase accessibility, and incorporate principles of universal design; which is where learning about executive functioning can come in.

However, I’d argue that it does NOT make sense to focus on an additional layer of strategy without a solid foundation relating to your specific content area; and not just with knowledge. With materials and curricular resources you have access to.

You can’t add the icing to the cake if the cake doesn’t exist.

I’d use that same thought process for therapists.

(This could include any of the related service providers, but I’ll use SLPs as an example.)

For many school SLPs, language therapy is the area they feel they’re lacking a foundation.

Developing a better system for language often creates the mental bandwidth for more ambitious projects.

With language intervention, we can make a significant impact by focusing on direct therapy, even within a pull-out model. This is not to say that other models are never appropriate or necessary, but students can make significant gains when we focus on improving protocols that can be done in a 1:1 or small group setting.

With executive functioning, things start to get more complicated.

This is not a “planning for therapy” kind of solution. It requires attention to the programming, the service delivery model, as well as the direct intervention. This means the therapist needs to be extremely clear on how to do executive functioning intervention in a 1:1 or small group model so they know how to explain their process to other people.

This is going to enable them to coach and train other people to use those same strategies and create scaffolding outside the therapy room.

This means therapists not only have to build their ability to conduct direct therapy sessions, they also have to learn how to document operating procedures and scalable clinical protocols, train and mentor others, function as a consultant, design and present information and training materials to others, or coordinate and plan instructional programming.

While administrators should be responsible for designing the programming; they can’t do their jobs effectively without help from those directly serving students, as principal Chris Dodge explains here.

I know it sounds like I’m putting a lot of responsibility on the related service providers, but many therapists find that expanding to other service delivery models makes them much more effective (which can take certain items off your plate in the long run).

It becomes not just about clinical skills, but leadership skills; which is a much larger undertaking. That’s why I have a comprehensive program for related service providers that helps them support executive functioning through direct therapy as well as other service delivery models.

That’s why for most clinicians who feel overwhelmed with both language and executive functioning; I typically recommend they tackle the language therapy issue first.

This isn’t about the research.

It’s about what’s going to help you get from point A to point B without burning yourself out.

The Scope and Sequence for Adult Learners

Adult learners need scaffolding just as much as kids do, and there are various ways to do that.

One is with the professional development model you’re using; which is why I advocate so much for team members to be building strategies and clinical protocols that can be shared with others.

If people are doing that, learning can be happening outside the “official” professional development seminars.

However in the context of this conversation, I’m thinking primarily of how I sequence the information and skills we want the adults to learn.

My goal is to meet the learner where they’re at so they can build and “stack” one set of skills at a time and enable people to develop automaticity in the foundational skills, so they can increase performance with more advanced skills in the future.

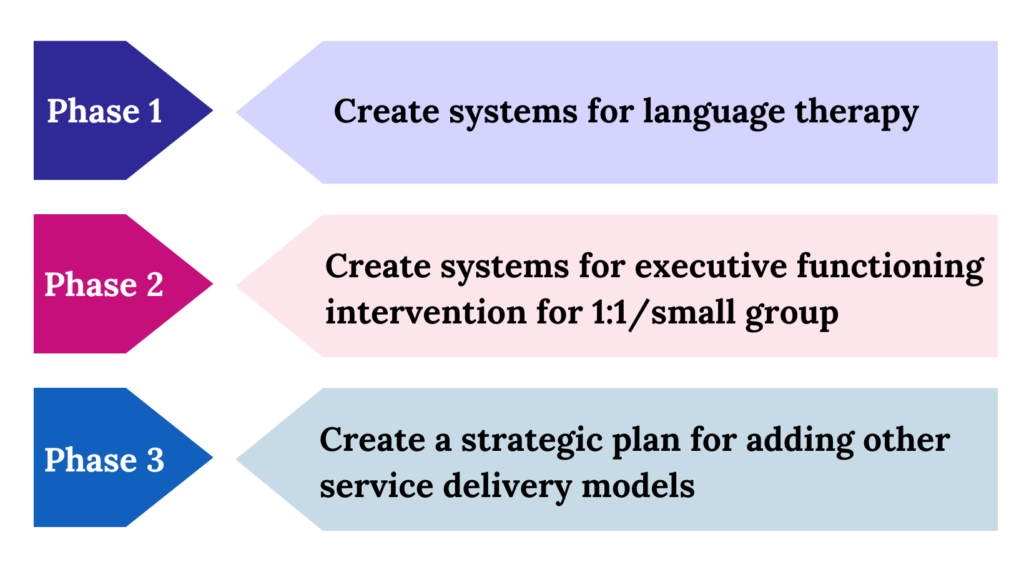

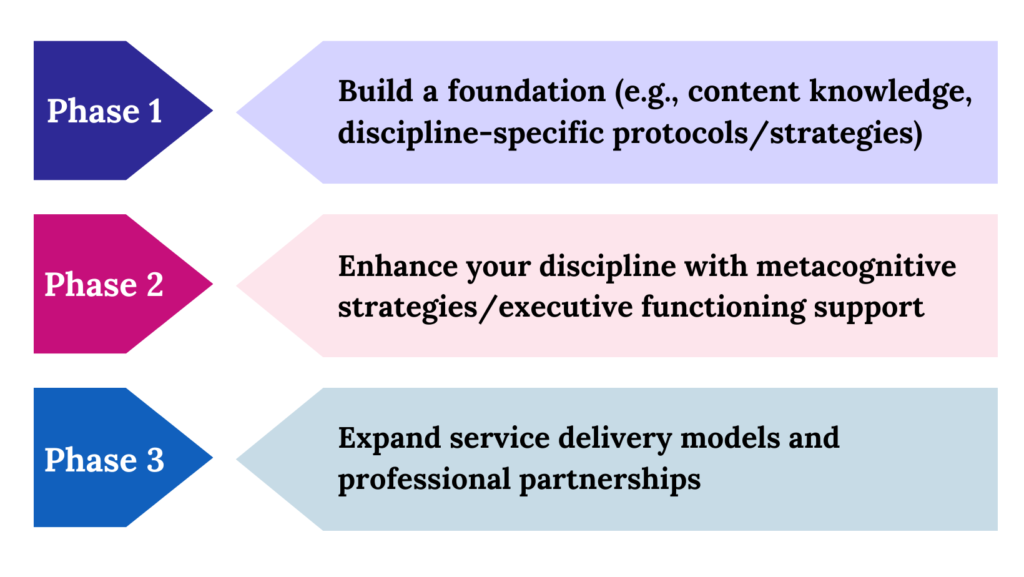

That’s why the sequence I recommend for the majority of school-based SLPs is:

We’re settling for “good enough” in the short-term in certain high priority areas in the interest of a bigger, long-term goal for ourselves clinically and professionally.

For example, the language therapy system I teach SLPs in Language Therapy Advance Foundations embeds tools like self-questioning and other metacognitive strategies, giving kids the opportunity to build executive functioning skills while doing word study.

I know that comprehensive executive functioning intervention involves much more than word study; but I’m taking opportunities to embed that kind of work now, knowing I’m going to cycle back to it in more depth later.; which is what I help related service providers do in the School of Clinical Leadership.

The same concept can be applied to other clinical and content areas.

For example, math curriculum expert, Jonathan Regino, shares ways that math can build foundational skills that support problem-solving in this interview.

Additionally, there are also plenty of opportunities to embed work on metacognition within reading curriculums, as literacy and school-turnaround specialist Cassandra Williams describes in this interview.

Occupational therapists also embed plenty of work on strategic planning and sequencing into their therapy protocols as well, which occupational therapist Maude Le Roux explained in episode 147 of De Facto Leaders

These steps may look slightly different for other clinical areas or for teachers. You can customize them to your content area or discipline.

Such as:

When you have multiple areas you’d like to build skills and systems, you can think of them like a backlog of projects..

As you work through them, you want to consider the research. You want to meet kids where they’re at and be in tune with their needs.

But sometimes the research and developmental levels don’t give us clear answers. And sometimes the “best” intervention plan isn’t feasible (which means it really wasn’t the best after all).

As I wrap up, I’m thinking back on what my dissertation chair, Dr. Julia Stoner said to me when I was just starting my dissertation research.

I had a grand plan and a massive project I wanted to do, and she said to me, “The best dissertation is a finished dissertation. Graduate first, change the world later.”

In other words, don’t let perfect be the enemy of good (and in my case, graduated).

When we make it all about the kids all the time, emotions get in the way, and we get so stuck on wanting things to be what’s “best” for the kids and what’s ideal.

Sometimes the best plan is a plan we can actually do.

References

Baron, L. S, & Arbel, Y. (2022). Inner speech and executive function in children with developmental language disorder: Implications for assessment and intervention. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 7(6), 1645-1659. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00042

Eberhardt, N.C. (2013). Syntax: Somewhere between words and

text. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 39(3), 43 – 48.

Fahy, J. K. (2014). Language and executive functions: Self-talk for self-regulation. Perspectives on language learning and education, (March, 2014), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1044/lle21.2.61

Larson, C., Gangopadhyay, I., Kaushankskaya, M., & Weismer, S. E. (2019). The relationship between language and planning in children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62 (8), 2772-2784. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-L-18-0367

Nippold, M. A. (2017). Reading comprehension issues in adolescents: Addressing underlying language abilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48, 125-131. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-16-0048

Scott, C. M. (2009). A case for the sentence in reading comprehension. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40, 184-191. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/08-0042)

Scott, C.M. & Koonce, N.M. (2014). Syntactic contributions to literacy learning. In C.A. Stone, E.R. Silliman, B.J. Ehren & G.P. Wallach Handbook of Language and Literacy, 2nd Edition (pp. 283-301). New York: Guilford.