“I only have 30 minutes a week with my students. How am I supposed to get to all these language skills?”

“I don’t even know where to start when it comes to treating language disorders.”

“I’m supposed to be the ‘language expert’, and I feel like an impostor. I’m so overwhelmed!”

I hear things like this from SLPs every month. And I used to feel this way myself.

Which is why if you’ve ever struggled with this, you’re going to love these principles I’m about to share with you.

Let’s face it: treating language disorders is no small task.

After working with hundreds of SLPs, I know that a lot of them don’t feel like they have tried-and-true system for language therapy.

A lot of these SLPs hate the uncertainty that comes with having no set therapy protocol.

Many times, they’re questioning their own level of “expertise” as they jump from skill to skill without making any measurable gains.

And even though they know they’re trying to cram too many things in to each session, they don’t know what else to do.

They feel like the HAVE to be jumping quickly from one skill to another because they’re afraid of missing something.

Why are we so overwhelmed when it comes to language therapy?

I used to feel just like the SLPs I mentioned above. I had a massive laundry list of language skills I was frantically cycling through.

😓Main idea

😓Supporting details

😓Summarizing and retelling

😓”Wh” questions

😓Pronouns

😓Verb tenses

😓Plurals and possessives

😓Categorization

😓Synonyms and antonyms

😓Following directions

And that’s just the beginning.

I never did a very good job teaching any of them because I was spreading myself so thin (and confusing my students even more).

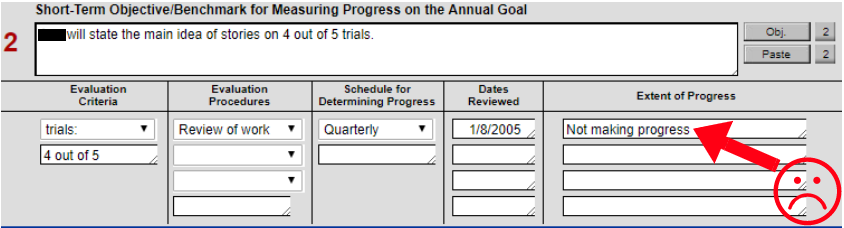

Needless to say, my progress reports were often looking like this:

I felt unprepared and unqualified, and I felt like nothing I did made any difference in my students’ lives.

I knew something had to change.

So I set out to find the perfect published language therapy program or curriculum…but my search came up short.

That’s when I realized that I had to put it all together on my own; and while I completed my doctoral research that’s exactly what I did.

I read through hundreds of studies and conducted a few of my own, I finally started to see some patterns.

As I studied the students on my caseload, I knew I had to find a better way to handle therapy sessions.

I only had 30-40 minutes per week with some of my students.

I had to stop jumping aimlessly from skill to skill, or they’d never make gains on anything.

I had to FOCUS only on the most important skills that would truly make an impact.

So I asked myself some difficult questions:

If I could cut through the clutter and ONLY focus on the skills that really mattered…how would that look?

What if I focused on LESS, not MORE?

What if I ONLY worked on the skills that had the biggest impact on overall language skills?

Would the world fall apart because I wasn’t doing “all the things” I thought my students needed?

Or would my intervention be more EFFICIENT and EFFECTIVE?

When I found the answer, I started getting students off my caseload because they’d met their goals, not because they’d plateaued.

And many other students made breakthroughs that finally got them their LRE.

Ever since then, I’ve been sharing those insights with other SLPs…and they’ve been able to do the same.

Today I wanted to share them with you by narrowing it down to three principles for highly-effective language therapy.

Principle #1: Less is more.

A lot of people assume that in order to help a student improve on a skill, you have to target it directly.

But you actually don’t.

Many of us notice a TON of language skills that our students can’t do.

We may even have teachers, parents, and other stakeholders coming to us with additional things we feel we need to add to our already massive list of things to target in therapy.

So let’s talk about what IS true.

First, direct instruction of specific skills and concepts works. Especially when it comes to language and vocabulary growth.

For example, in multiple studies, children have been able to learn and retain vocabulary knowledge when given direct explanations of words compared to exposure alone (Biemiller & Boote, 2006; Marulis & Neuman, 2010).

Children also learn vocabulary through exposure, but kids with disabilities impacting language like the ones we treat require explicit instruction like the kind I describe in this vocabulary booster for SLPs.

But there are a couple caveats to direct instruction.

First, it’s not possible to teach our students everything.

Second, its not necessary directly target every skill because some skills will facilitate growth of other skills if we prioritize on the right skills.

This brings us to something called the 80/20 rule; or the Pareto Principle.

The Pareto Principle states that on a given task, 20% of the work we’re doing accounts for 80% of the results (Kruse, 2016).

In other words, about 20% of what we’re doing is actually working. That means that the remaining 80% isn’t doing much, which means we can eliminate it.

If we can figure out what our “20%” is for whatever we’re doing, we can laser-focus on the skills making the biggest impact on outcomes.

This way, we can multiply our impact, because we have the energy to devote the things that really matter.

In other words, you focus on the small percentage of treatment techniques (this would be your 20%) that would account for 80% of your students’ gains.

This is how you help your students get to their LRE and finally make breakthroughs…without sacrificing your personal life (and your sanity).

Principle #2: Knock down the first domino.

Now of course, the 80/20 principle sounds sexy, but knowing how to find that “20%” is easier said that done.

In order for us to truly cut back on the skills we’re addressing with our students, we need to know what those high-priority language skills are that will facilitate growth of others.

I call those high-priority skills “the first domino”.

In other words, we want to focus on the ONE skill that will be the most impactful so you can actually give your students enough time to make measurable gains.

Which comes to the million dollar question: “What is that ‘first domino’ (a.k.a. ‘high-impact 20%’) that will help us start building momentum”?

But when I was able to answer that question, everything turned around for my students.

As I studied the patterns in my language referrals and dug in to the research, I found a pattern.

My students just didn’t have the word knowledge to keep up with the pace of the curriculum, and the gaps were getting wider and wider. They were floundering in school because of it.

Why?

Because if you don’t know at least 90-95% of the words in a text, you won’t be able to understand it (Nagy & Scott, 2009).

We can actually predict which students will be struggling and which ones will be strong readers by the time they get to high school by looking at their vocabulary scores in early elementary school (Scarborough, 2001; Zipke, 2007).

And here’s the sad part for students with language disorders:

Typically-developing children can learn anywhere from 3000-5000 words per year in the early elementary years (Biemiller & Boote, 2006).

But children with weak language skills may only learn 300-900 words per year (Cain, 2007).

That means that if you compared the worst possible scenario for a student with a language disorder to the best-case scenario for a top-performing student, differences in vocabulary growth are only going to widen over time.

Many interventions focus on high-level comprehension strategies, following directions, summarizing, and retelling.

That approach often doesn’t work well for our students because we’re focusing on the SYMPTOM not the ROOT CAUSE of the issue.

Research has shown us that students with language delays aren’t likely to respond to comprehension strategy instruction if we don’t address the underlying language skills holding them back (Nippold, 2017).

The bottom line: Students aren’t going to be able to comprehend entire paragraphs and summarize the “main idea” if they don’t have solid comprehension at the word and sentence level.

And they can’t do either of those things with weak word knowledge.

This explains why so many students with language disorders don’t respond to traditional “comprehension” instruction focused on things like stating the main idea, inferencing, answering “wh” questions, or following directions.

So what’s the culprit behind these comprehension issues? You guessed it: Vocabulary.

That’s why vocabulary intervention is your “20%”.

I call it the “first domino” because when you “knock it down” by addressing it correctly, you’ll find that you’ll be building a massive amount of momentum.

This momentum comes when you finally give your students a solid foundation for high-level comprehension.

That momentum allows you to knock the other “dominos” down much more easily later on…and sometimes they even might improve on their own once that foundation has been formed.

In other words, either those “high-level” comprehension skills improve on their own…or you give your students the skills they need to finally make progress with comprehension strategy instruction.

I share a way to start “knocking down” that first domino in this free Vocabulary Booster for SLPs.

Principle #3: Make it meta.

So now that we’ve identified that vocabulary is the “first domino” that allows us to focus on the skills that will make the biggest impact, we can move on to how that’s done.

How do we break through those dreaded therapy plateaus?

The vocabulary gap between where your students are and where they need to be is getting wider every day.

So wide, in fact, that we’ll never be able to teach our students all the words they need to know.

But here’s the tricky part: Students with language disorders are highly dependent on direct, explicit instruction.

So if they NEED direct instruction how do we close that gap if we can’t teach them all the skills they’re lacking?

Answer: We get “meta”.

Being “meta” refers to thinking or conscious awareness.

Because “cognition” refers to our thought processes, “metacognition” is our awareness of our own thoughts and the way we learn. “Metalingusitic” refers to our awareness of our thoughts relating to language, its rules, and how we use it (Roehr, 2008; Zipke, 2012).

One of the biggest areas of struggle for our students with language disorders is that they have weak metacognitive and metalinguistic skills.

That means our therapy time needs to focus on getting “meta” about language by drawing their attention to linguistic rules and details that may help them learn words independently.

Our students often haven’t “learned how to learn”, which is why they need so much direct instruction. But the good news is that students with language disorders can improve their metalinguistic awareness skills with direct training (Zipke, 2012).

When we teach students to pay attention to linguistic details, they gain metalinguistic awareness (Kucan, 2012; Zipke, 2012).

Research has shown that metalinguistic awareness training can result in better retention of vocabulary, and can facilitate independent word learning (Zipke et al., 2009; Zipke, 2012).

And in order for that “meta” focus to actually build vocabulary and facilitate independent word learning, it needs to be focused on linguistic skills that contribute to vocabulary growth.

Those “Essential 5” meta skills you need for strong vocabulary are: phonology, orthography, morphology, syntax, and semantics (Kucan, 2012).

In order to perform well in a school setting, you need knowledge of all 5 areas. Here’s how each one of them ties back to vocabulary:

Here are some examples of how we can add a “meta” focus:

- Teaching students that words are made up of phonemes that can change meaning by comparing minimal pairs (Kucan, 2012).

- Analyzing meanings of root words, and how their meanings and part of speech change when we add prefixes or suffixes (Cunningham, 2009).

- Exploring differences in homonyms or homophones and studying how spelling differences or contexts signal changes in meaning (Zipke, 2012).

- Explaining meanings of words and using them in sentences to draw awareness to syntactic structures used for different parts of speech (Marinellie & Johnson, 2002).

- Discussing semantic features such as function, physical characteristics, location, associations to help students have more detailed understanding of words (Beck & McKeown, 2007).

Now of course, this is only the tip of the iceberg.

I’ve spent the last 14+ years both studying the “meta” framework for building vocabulary I’ve just described above…so of course this is just the beginning.

Now I do take a deep dive in to the exact metalinguistic strategies to use under each of the 5 linguistic components in my program, Language Therapy Advance; but I wanted to leave you with something today that would help you start adding a “meta” focus to your therapy right away. It’s called “The Power of Meta: Vocabulary Booster”.

The Power of Meta: Vocabulary Booster

The Power of Meta: Vocabulary Booster includes 30 pages of tools to help you address vocabulary and syntax all at once, so students develop the necessary metalinguistic skills needed to define words.

It will walk you through a set of evidence-bases strategies that build metalinguistic awareness skills of both semantic and syntax, so your students retain meanings of words and have a deeper understanding of age-appropriate vocabulary.

It includes the following tools:

Tool #1: Meta Definitions Rating Scale.

Unlike many other formal measures, this vocabulary rating scale gives you a deeper understanding of your students’ vocabulary knowledge beyond just naming and identification. It’s also useful for measuring progress in therapy over time, and flexibility to measure your students’ knowledge of vocabulary relevant to their curriculum or environment.

Tool #2: 4 Noun Definition Syntax Templates.

When students struggle with vocabulary, we need to help them grasp both the content (word meanings) AND the format (syntactic structure) of definitions. These printable templates will help your students easily study word definitions and retain their meanings. You can reuse these as often as you want with words that are appropriate for your students’ ability levels.

Tool #3: 96 Tier 2 Nouns Flash Cards.

When we teach our students definition format, we need to practice using words that will help students learn more difficult concepts. Using Tier 2 words as targets can help us build curricular content knowledge and target syntax all at once. These flash cards include nouns organized by grade level for grades K-5.

Plus two bonus sections:

This includes an orthographic awareness worksheet to build spelling skills, plus and other supplemental resources to boost your students’ meta skills.

>>>Click here to download the free 30-page Vocabulary Booster for SLPs.<<<

References:

Beck, I.L., & McKeown, M.G. (2007). Increasing young low-income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 107, 251-271. doi:10.1086/511706

Biemiller, A., & Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 44-62. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.44

Cain, K. (2007). Deriving word meanings from context: Does explanation facilitate contextual analysis? Journal of Research in Reading, 30, 347-359. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9817.2007.00336.x

Cunningham, P.M. (2009). What really matters in vocabulary: Research-based practices the curriculum. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Kruse, K. (2016). The 80/20 rule and how it can change your life. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2016/03/07/80-20-rule/#32f956973814

Kucan, L. (2012). What is important to know about vocabulary? The Reading Teacher, 65, 360-366. doi:10.1002/TRTR.01054

Marinelle, S. A., & Johnson, C. J. (2002). Definitional skill in school-age children with specific language impairment. Journal of Communication Disorders, 35, 241-259. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9924(02)00056-4

Marulis, L. & Neuman, S. (2010). The effects of vocabulary intervention on young children’s word learning: A meta-analysis. Review of educational research, 80, 300-335. doi:10.3102/0034654310377087

Nagy,W.E., & Scott, J. (2000). Vocabulary processes. In M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P.D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research Volume III (pp. 269-284) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Nippold, M. A. (2017). Reading comprehension issues in adolescents: Addressing underlying language abilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48, 125-131. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-16-0048

Roehr, K. (2008). Linguistic and metalinguistic categories in second language learning. Cognitive Linguistics, 19, 67-106. doi: 10.1515/COG.2008.005

Scarborough, H.S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to letter reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D.K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp.97-110). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Zipke, M. (2012). First graders receive instruction in homonym detection and meaning articulation: The effect of explicit metalinguistic awareness practice on beginning readers. Reading Psychology, 32, 349-371 doi: 10.1080/02702711.2010.495312

Zipke, M. (2007). The role of metalinguistic awareness in the reading comprehension of sixth and seventh graders. Reading Psychology, 28, 375-396. doi: 10.1080/02702710701260615

Zipke, M., Ehri, L.C., & Cairns, H.S. (2009). Using Semantic Ambiguity Instruction to Improve Third Graders’ Metalinguistic Awareness and Reading Comprehension: An Experimental Study. Reading Research Quarterly, 44, 300-321. doi