I spend a lot of time talking about languages. After all, my site is all about building better language skills in children with disabilities.

But today, I’m going to talk about another kind of language. One that doesn’t focus syntax or morphology.

However, it does focus on one key verb.

That verb is “love.

I’ll also be reviewing a book that should be on your bucket list if you work with children or have children of your own.

For SLPs, it’s a definite must-read.

But let’s get back to that word again: “Love”

Ask someone to define the word. You may hear people say it’s a “thing” or a “feeling”.

And I know I’m getting caught up in semantics here since that’s my nature, but there’s a problem if you think of it solely as a noun.

The problem with saying that love is a feeling is that this implies that it’s just something that happens to us passively. That we don’t have to actually do anything to “love” someone else. And this is where we’re going wrong.

Now I know as SLPs, we like to talk about multiple meaning words and flexible word use. We like to explain to kids that a word can mean one thing in one context and something slightly different in another.

Or that a word can be a noun in one situation and a verb in another.

So it’s true that love is sometimes a noun.

But we won’t be able to form relationships with our friends, family, and students if we don’t realize that in MOST contexts, love is actually a verb.

It’s something that we DO. Actively. And it’s something that takes work. Sometimes we need to “love” someone when we don’t feel like it.

I’ve heard the saying that when it comes to work in educational and clinical fields, that the kids that are the hardest to love are the ones who need it most.

And we’ll never get anywhere in therapy with these kids if we don’t understand that.

Let me ask you some questions to show you what I mean.

When was the last time you listened to someone you didn’t trust?

Have you ever willingly obeyed someone when you didn’t feel understood?

Have you ever followed advice from someone when you weren’t sure if they really cared about you?

Now think about the opposite scenario. Think of those people who are hard on you, but made a lasting impact on your life.

They may have made you uncomfortable at times and pushed you; but you could take it from them because of trusting relationship you had with them.

They earned the right to give you tough love when you needed it because they’d put in the work to build your relationship ahead of time.

This brings us to the book review.

The Five Love Languages of Children, by Gary Chapman and Ross Campbell, M.D.

The first book that made the concept of love languages widely known was The Five Love Languages: The Secret to Love that Lasts, by Gary Chapman.

Chapman wrote this book to help married couples strengthen their relationships by keeping their partner’s “emotional tanks” full.

After the love languages concept became popular, Chapman published The Five Love Languages of Children with Dr. Ross Campbell.

This book, while written for parents, is also highly relevant to professionals working with kids. That is why I’m reviewing it for you today.

This is the basic set of beliefs Chapman explains throughout the book:

- Children will act like children, which means their behaviors are often childish and unpleasant.

- If we do our part and love them (despite their unpleasant, childish behavior), they’ll eventually mature and grow in to well-adjusted human beings.

- If we only show love when children are being “good”, we run the risk of delaying this maturation and development of self-control.

- When we only love children when they’re meeting our expectations, they’re more likely to feel anxious and incompetent.

- When it comes to managing behaviors, children are much more likely to comply with what we ask when their “emotional tanks” are full.

When children’s emotional tanks are empty because we haven’t been attentive to showing them affection in their preferred mode, we become more and more likely to see behavior problems.

These tenets may make you rethink the traditional sticker charts for rewarding good behaviors. Relying on external rewards may get some compliance in the moment, but that temporary bribe often doesn’t result in true ownership of the behaviors beyond that point.

Chapman starts out the book with a case study about a bright student named “Ben”. His parents came to one of Chapman’s workshops, and they’d mentioned that recently Ben had been acting up in school and becoming increasing clingy. Ben’s parents were worried that he was developing a rebellious streak.

When Chapman dug in to the problem further, he discovered that due to some recent changes in his parents’ work schedules, they weren’t spending as much time with him.

Ben’s issue wasn’t that he was a rebellious kid. The issue was that his emotional tank was empty. His love language was “quality time” and his parent weren’t speaking it to him enough.

They initially didn’t see the problem, because they were showing him affection in other ways that THEY saw as “loving” him. But they weren’t expressing in in the way that he needed in order to feel whole.

Chapman and Campbell explain in the book that this occurrence is not uncommon. Many behavior problems arise when children have a depleted emotional tank. This is when discipline problems are likely to surface and relationships start to deteriorate.

So why is love a verb?

Because in order to show a student we care, we have to take actions needed to communicate in their “love language”. It’s not simply a feeling we have; rather its a set of actions we do for someone else to show them they’re important to us.

What’s your “love language”?

There are actually tests you can take online, such as this one here, that help you determine what your “love language” is. Most of us can figure it out by just reading about them. We may have to do a bit of digging to pinpoint the love languages of other people in our lives (and that’s something that’s discussed in the book).

Unfortunately, Chapman explains that most of us give affection they way we would prefer to get it, not the way that others need it.

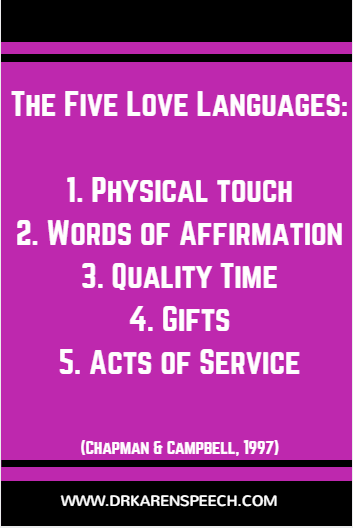

This requires a bit of detective work on our part, but the first step is defining each of the five languages.

That’s what the authors do in the first half of the book; so I’ll go through each one of them individually and explain how you can apply it as an SLP.

Physical touch

If we’re applying this concept to your own children, this is pretty straightforward. People who speak physical touch as their primary love language are the snugglers who always want a hug and a kiss, or who crave physical closeness.

Obviously, when we’re talking about how to use this with the kids you serve, those behaviors aren’t all appropriate.

Depending on the situation (and be careful with this), a hug might be appropriate for a student. But there are other “safer” ways you can show these students you care.

These students may want to sit right next to you when you’re working with them. They may need a hive five or a pat on the back.

You may want to get their parents involved to make sure that they’re getting the physical affection at home (the kind that might not be appropriate for a clinician-child relationship) so that they come to school with a complete tank.

Words of Affirmation

These are the kids who need lots of verbal praise. Whether it’s telling them that they did a good job, or complimenting their new haircut, their emotional bank is full when you show them with words that they’re important to you.

Now with kids who have disabilities; especially disabilities that impact language processing, this presents an interesting challenge.

Obviously we’d want to use language that we know our students can understand, and that isn’t wordy or overcomplicated. These are the kids who need a lot of verbal encouragement and acknowledgement (and not just when they are “being good”).

Quality time

People who speak quality time as their primary love language need human connection in order to feel loved.

Have you ever had a student who always wanted to keep chatting even after your session was over? Or maybe you have a child who always wants to stop you in the hall to talk?

These are the kids who speak “quality time” as their love language.

The sad part is that a lot of kids who speak quality time as their love language are in home environments that don’t allow them to get what they need. Thankfully, you as the SLP are perfectly positioned to be one of the people who helps fill their “emotional tank”.

This is why a little small talk before and after a session can be a good thing, even if it means cutting out a few minutes of “real work”.

Gifts

This one is interesting to me, because many educators fall on one or the other side of the spectrum as far as their philosophy.

Some depend highly on external reinforcers and give “gifts” regularly to students as rewards for good behavior, while others are totally against it because they feel it deters from internal motivation.

But is it possible to have a middle ground?

According to Chapman and Campbell, there is a way to incorporate the practice of giving kids tangible things as part of a behavior plan, but it isn’t a traditional operant conditioning approach (the kind that rewards kids with positive reinforcement).

Rather, when kids have “gift giving” as one of their love languages, these little “gifts” shouldn’t be used conditionally as a reward for good behavior.

Rather they should be given “just because” to show we care. It’s like you wouldn’t expect your spouse to give you flowers as a reward for doing the dishes; you’d want them to do it to say, “Hey, I was thinking of you and I thought you would like this.”

These gifts don’t have to be extravagant. It could be as simple as a sticker, a special pencil, or even a nice note.

Acts of Service

People who speak acts of service feel loved when we do things for them. This means that when their emotional tank is empty, they may be likely to ask for help when they don’t really need it.

What they may be really asking for is attention.

In romantic relationships, this might include showing your appreciation for your significant other by taking care of the kids or doing things around the house. When it comes to kids, it might be through taking the time to help them with their homework or taking them to sports practice.

As SLPs, you are literally performing an act of service as your job; so you’re perfectly positioned to fill this need for a lot of kids.

The great thing is this “help” doesn’t always have to be with school-related tasks; it could be as simple as holding a door or pulling out a chair for a student.

The rest of the book focuses on applying the framework to life, including things like:

- How to discover a child’s love language.

- How to discipline children in a way that shows unconditional love.

- How to apply the love languages framework to a learning environment.

- How anger can impact the way we express and receive love and how to help kids deal with this emotion.

- How to speak the love languages in single parent households and in marriage

A detailed set of discussion questions are included for each chapter, so I highly recommend this book for parenting or professional book studies.

You can get more information about this book here.

Do you want to get more articles and resources just like this one to help you make therapy breakthroughs?

If so, click on the button below to join my mailing list: