Literacy intervention for SLPs treating students with language disorders is a hot topic these days.

The problem is that there isn’t a clear consensus about where SLPs should intervene which makes it really hard to figure out what we’re “supposed” to be doing.

That’s why today I’m going to share some important research findings that can shape literacy intervention for SLPs and clear things up.

But on the surface, what I’m going to say may sound a bit backwards…

You see, a lot of commercially available materials for SLPs focus on “comprehension strategies”.

So do standard curricular materials.

But if you’ve been working on comprehension with your students, you may have already realized that they’re STILL struggling.

It can see like you’re fighting an uphill battle, barely making headway.

The reason: You’re treating the SYMPTOM, not the cause.

Now I know this sounds a little backwards, because comprehension is the point of reading and listening in the first place.

And we certainly don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater here and disregard this type of work 100% of the time.

But if you’ve ever wondered if your interventions are lacking…if your students are missing something…or if there’s another piece to the puzzle…

Then you’re going to get massive clarity as you read what I’m about to share…

And when you stick with me until the end of this research review, it will all start to make sense.

This study I’m about to share has been around a while; and I’m reviewing it for you because sometimes we just need a little validation for what we’re doing in the therapy room.

It’s like we’re being reminded of the reasons we do what we do in the first place (because sometimes even though we “know” something works, we might forget where we learned it in the first place).

Back in 1995, Gillon & Dodd did a study investigating the impact of spoken language training on spoken language tasks and reading comprehension. They also compared the impact of the training on phonological awareness intervention to an intervention that targeted oral semantics and syntax.

Essentially, this is what Gillon and Dodd wanted to know:

1. If we give children with language impairments and reading difficulties training in spoken language in their deficit areas (e.g., semantics, syntax), will those areas get better?

In other words, will our therapy actually improve those skills we are training?

2. Will those interventions (focused on spoken syntax and semantics) impact reading comprehension?

So we not only want to know if this spoken language intervention will improve “speech and language”. We also want to know if it will carry over to another task reading, without direct training that involves “teaching reading”

3. Is phonological awareness training more effective than training spoken semantics and syntax?

In other words, is what’s the most efficient form of literacy intervention for SLPs? What pieces make the biggest impact? Is one piece superior to another?

Let’s look closer and see.

Gillon and Dodd used a form of single-subject design (an alternative treatment design) with 10 participants (ages 10-12) with diagnosed language impairments and reading difficulties.

They divided participants in to 2 groups:

Program 1: Participants participated in a training program focused on phonological awareness skills such as segmentation, blending, and manipulation of speech sounds in syllables.

Program 2: Participants received training focused on semantic and syntactic skills.

This included tasks such as identifying complete sentences, forming and reducing compound/complex sentences, cloze activities, perceiving inconsistencies within sentences, semantic webbing, and forming sentences with key vocabulary.

Results showed that participants in Program 1 significantly increased phonological awareness skills after treatment.

Participants in Program 2 significantly increased semantic and syntactic skills.

These differences in pre to post tests showed that both programs were effective in improving the skill that was being trained: so teaching phonological awareness improved phonological awareness, and teaching semantic and syntactic skills improved semantic and syntactic skills.

That seems like it would be obvious, but it’s actually pretty important to point this out.

There are actually times when we train someone to do a specific skill, and they still can’t do it afterwards; so these results show that phonological awareness training AND training on spoken language skills both improve the skills they’re targeting.

Next, Gillon and Dodd looked to see if reading skills improved.

They found that phonological awareness training was more effective in improving word reading abilities than semantic-syntactic training.

This indicated that for strict decoding skills, phonological awareness is still a critical piece; and can’t necessarily be replaced by other programs that focus on other language-based skills alone.

However, researchers also found that students in BOTH programs increased their performance on reading comprehension skills, even though reading comprehension strategies were not directly taught to any of the participants.

So what can we make of these results, and what does this mean for literacy interventions for SLPs?

For one, students with weak skills in one area may be able to compensate by recruiting skills from another area.

For example, increasing a students’ syntactic and semantic knowledge may improve their overall comprehension skills; even if we don’t directly target any other comprehension strategy (e.g., stating the main idea, recalling details/events).

This means that what we do in “speech therapy” to target syntax and semantics has potential to improve reading comprehension; even if it emphasizing spoken language more so than written.

I’m NOT saying literacy intervention for SLPs doesn’t need to incorporate direct work on orthography (it should).

I AM saying that the work we do to improve oral language may be more powerful that we think.

Now the next point: Weak phonological awareness skills can still hinder a students’ ability to compensate with other language skills.

Remember that even though reading comprehension improved for both participant groups in the study; phonological awareness training was still more effective than spoken language training when it came to strict word decoding.

So this mean working on semantic and syntax can improve comprehension…but there’s a catch. It may be difficult for students to recruit these newly developed language skills if the cognitive load of decoding is too high.

In other words, students need to have adequate phonological awareness skills to decode in order for work on semantics and syntax to improve reading.

Targeting semantics and syntax may still improve spoken language skills even if reading doesn’t improve; but we will only see those skills benefit reading if phonological awareness skills are intact.

That goes the other direction too. If students are going to benefit from work on phonological awareness, they need to have adequate vocabulary skills to know the meanings of words they’re reading. They need to make sense of the sentence structure.

And finally, just like students need adequate work on all three of these skills (phonological awareness, semantics, syntax) in order to benefit from work on high-level comprehension strategies, like I described in this article here.

Now, let’s go back to that bold statement I made at the beginning:

Should SLPs stop working on reading comprehension? Does this need to be a part of literacy intervention for SLPs?

The short answer is “Yes”, but not in the way you’d think.

Technically, if we are building a FOUNDATION that’s going to reduce the cognitive load required in reading (for example, when decoding), we are freeing up resources that can be devoted to high-level comprehension.

If we don’t address these foundational skills, no amount of “stating the main idea” or inferencing questions are going to help.

They simply won’t be in a place where they can benefit from that type of work; at least not without addressing the root cause first.

What this means is that just because you aren’t directly working on comprehension (e.g., explicitly talking about comprehension strategies) doesn’t mean you aren’t addressing comprehension.

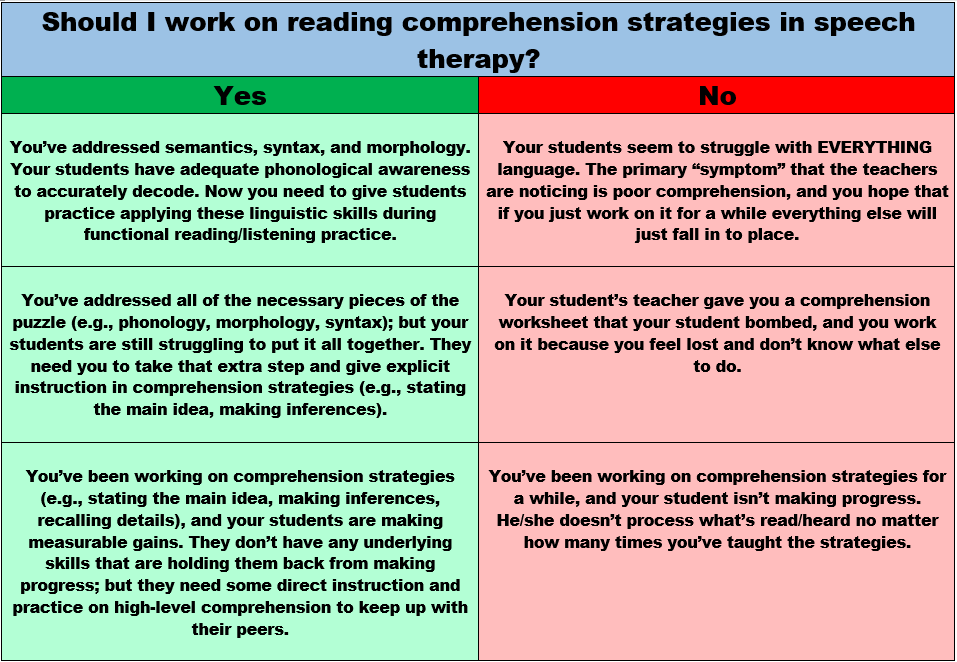

Here’s a quick visual that will help you problem-solve and determine when literacy intervention for SLPs should target high-level comprehension work:

If you liked this article and want to get more like it delivered straight to your inbox, sign up for my mailing list here. When you sign up, you’ll get a free Tier 2 Words download so you can start targeting your students’ spoken language skills right away.

References: