This is the third installment in Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy, where I’ll be giving you some sentence structure goals for speech therapy. In the first part, I shared a “base goal” for syntax that defines the “big idea” and ensures that you have a goal you can measure.

In the second article, I talked about sentences with passive verbs, one of the challenging sentence structures for students with language disorders (Zipoli, 2017).

I also shared some possible sentence structure goals for speech therapy and an activity for targeting syntax.

In this third article, I’m going to tell you another syntax goal you can add to your IEP goal bank that relates to another challenging sentence type.

So let’s get to that next sentence structure that’s difficult for student with language disorders:

Sentences that have adverbial clauses and temporal or causal conjunctions

I will admit that before I worked on this one, I had to look some of these things up.

I don’t just walk around all day thinking about adverbial clauses if ya know what I mean (even though I use them without batting an eye).

This is actually part of our problem…this stuff is so easy for us we don’t always know how to break it down for our students.

Before we get to writing the ideal sentence structure goal for speech therapy, let’s define some key terms.

Clauses are groups of words with a subject and a predicate. Some can stand alone as sentences, while others can’t.

An independent clause is a clause that can be a stand-alone sentence. For example, “The children ate breakfast,” or “Let’s go home.”

A subordinate, or dependent clause cannot stand alone. It must be attached to an independent clause. For example, “because it was morning,” or “after we go home.”

Adverbial clauses are clauses that contain adverbs. The adverb is often describing how something is done. For example, “if we go home soon”, or “because you moved slowly.”

An adverb is a word that describes a verb, adjectives, or another adverb. Examples include words like “randomly”, or “excitedly”; or from the previous example, “soon”, and “slowly.”

Temporal conjunctions are words that connect clauses or words within clauses (like the subject or verb of a sentence). They explain “when”. This includes words like “before”, “after”, or “while.”

Causal conjunctions also connect clauses or words, but they explain “why”. This includes words like “because”, “since”, or “therefore.”

Part of writing effective sentence structure goals for speech therapy is having a firm grasp on all of these terms so you can explain them to your students.

At first glance, it’s easy to see why this sentence structure might be difficult for students with language processing problems.

There’s a lot of different terms they need to process at once all within one sentence. If they misunderstand just one of those things, it can throw everything off.

The key for us defining what exactly should be in the sentence structure goals for speech therapy is understanding which part is tripping them up.

Let’s see if YOU can pick out each element in a couple of examples. Here’s an example of a sentence with an adverbial clause and a causal conjunction.

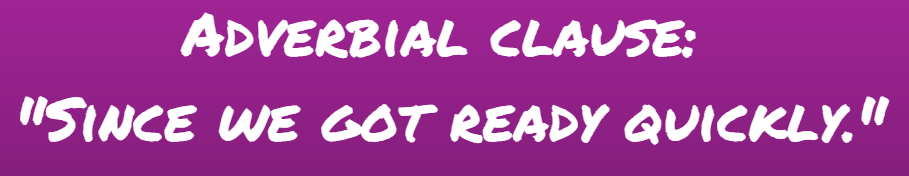

Since we got ready quickly, we had time to go out to breakfast.

See if you can pick out the following:

1.Causal conjunction

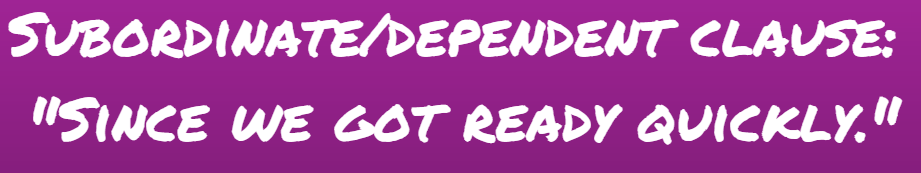

2.Subordinate/dependent clause

3.Adverbial clause

4.Independent clause

Ready for the answers?

In this sentence, the conjunction “since” explains why we were able to go out to breakfast.

This has a subject and a predicate, but can’t stand alone without the attached dependent clause. In my writing on this blog, I break this rule all the time and start sentences with conjunctions.

It’s become more acceptable in conversational speech to break this rule, or even during less formal written language (like blogs). But technically, it’s not syntactically correct (see, I just did it right there). It’s important our students can code switch and make that distinction.

The dependent clause is also an adverbial clause, because it describes how we got ready (quickly).

There’s a subject and a predicate, and this could function alone as a sentence. Even though the dependent clause isn’t stated in this sentence type, we need it because the subordinate clause can’t stand alone (unless you’re a rebellious blogger breaking the rules).

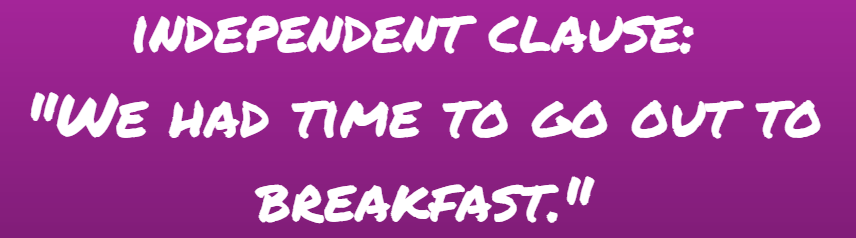

Just to make sure you have a clear picture of how to apply this to writing sentence structure goals for speech therapy, let’s do one more example, this time with a temporal conjunction. Here’s your example, following by the examples:

I passed my test after studying consistently all semester.

Before we add more sentence structure goals for speech therapy to that IEP goal bank, let’s think about why this type of sentence is so difficult.

Students with language processing issues may be reliant on “order of mention” (Erickson, B., 2016; Owens, 2006; Paul & Norbury, 2012; Westby, 2012).

Let’s look at our first example so I can show you what I mean:

“Since we got ready quickly, we had time to go out to breakfast.”

In this sentence, the cause (getting ready quickly) came before the result (having time to go out to breakfast).

We could rearrange these clauses and say:

“We had time to go out to breakfast since we got ready quickly.”

The meaning is the same, but the result comes before the cause. In either cause, we need to pay close attention to what is causing what.

Students who are overly reliant on order of mention will only notice the order of events. They may not fully understand the function of words like “since”, which is why I often write sentence structure goals for speech therapy that mention conjunctions directly.

Students may also not grasp the meaning behind the clauses that tells us which event would logically cause another; another consideration when making an IEP goal bank.

Relying on order of mention can be an even bigger problem when we have a sentence with a temporal conjunction.

Let’s go back to our temporal conjunction example:

“After studying consistently all semester, I passed my test.”

In this instance, the events are mentioned in chronological order. First I studied, then I passed my test. You can pay attention to the order of events and get the gist.

Now let’s switch it:

“I passed my test after studying consistently all semester.”

We need to pay attention to the word “after” and hold the information from the clauses in our working memory. Then we need to mentally flip the two events around so we understand that the studying came before the passing.

This is considerable harder, especially if you’re expecting to hear things in the order they happened. Another case for including conjunctions in sentence structure goals for speech therapy.

Another issue is that your students might not process modifiers like adverbs, so words like “consistently” could be difficult as well.

They might not be able to explain why I was able to pass my test, nor would they be able to explain how you would need to study in order to pass. They may not notice that the word “consistently” explains that I was studying often, and not doing it carelessly.

Because our students are struggling immensely, we have our work cut out for us.

(Did you see what I did there? Causal conjunction: because, adverb: immensely, adverbial clause: because our students are struggling immensely. I know, I need to get out more).

So let’s move on to writing these sentence structure goals for speech therapy.

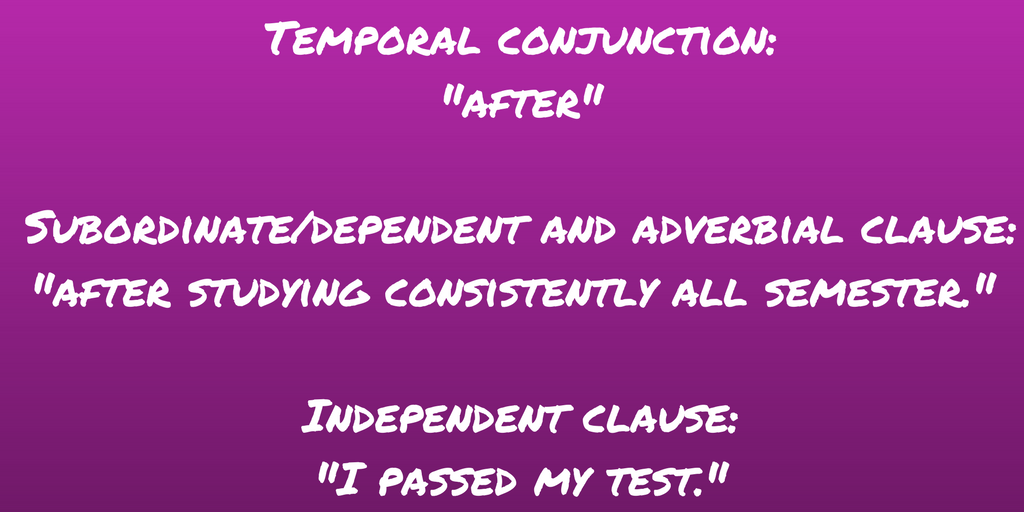

Our base goal for targeting syntax was:

“Student will say/write sentences.”

One of the challenges for our students will be using adverbs, so we need to think about how we’d fit that in to sentence structure goals for speech therapy. I have never written an individual goal for adverbs. When I have worked on them, I usually addressed them under this goal:

“Student will use grade-level (or age-appropriate) vocabulary words in sentences with 80% accuracy.”

This goal could include target words from varying classes, so it allows me to target more than one word type. You could make it more specific and say something like:

“Student will use grade level vocabulary words in sentences with correct grammar/syntax with 80% accuracy.”

Because we’ve included both the morphosyntactic and semantic component here, we could track progress on adverbial clauses with temporal/causal conjunctions under it.

This goal would meet the “good enough” criteria, but I’m not crazy about it. I think we could make it a little more focused.

When syntax is an issue, part of the problem is that students tend to overuse simple sentence forms (Zipoli, 2017). Because of that, we need to encourage them to use more compound and complex sentences.

One of the critical skills required for creating more sophisticated sentences is understanding and using conjunctions; so this is what I usually state in my sentence structure goals for speech therapy.

That might look like this:

“Student will say/write sentences with conjunctions on 4 out of 5 trials.”

We still use conjunctions in simple sentences (for example, the word “and” in this sentence: “Mom and dad went to the store.”), so this goal could cover conjunctions in simple, complex, and compound sentences.

If you wanted your goal to be more specific and clarify that you want a complex sentence, you could say any of the following:

“Student will say/write complex sentences with conjunctions on 4 out of 5 trials.”

“Student will say/write complex sentences with temporal/causal conjunctions on 4 out of 5 trials.”

“Student will say/write complex sentences with temporal/causal conjunctions and adverbial clauses on 4 out of 5 trials.”

As you can see, we can mix, match, and pick apart these skills to death. That’s why I recommend making it specific enough, but not so specific that you have too many goals.

In a way, these are a little redundant because we need a temporal or causal conjunction to make a complex sentence (so we could in theory just list one skill or the other skill, rather than both). But sometimes it’s nice to have it all written out to remind you why you’re working on the IEP goal in the first place.

With most of my students, I go with the first example (“Student will say/write complex sentences with conjunctions on 4 out of 5 trials.”) because in encompasses multiple sentence types, and sometimes my students need work on using conjunctions with simple sentences before we move to complex.

Leaving this room for flexibility covers my bases enough that I know what I should track, but also leaves it open for progress throughout the year.

Last but not least, are you ready for your ridiculously simple speech therapy strategy for syntax?

It’s called a “sentence starter” (Zipoli, 2017).

What you do is start a sentence for your student and have them finish it. Eventually, the hope is that you will be able to fade this prompt.

This is particularly effective for students with language processing issues because they tend to stick to simple sentences.

Starting the sentence for them gives them a structural cue that can help them come up with a more sophisticated sentence.

One way to do this is to use a conjunction as a sentence starter.

For example, if you wanted the student to tell you that they went to bed early because they were tired, you could say:

“Because…”

And hope they say: “Because I was tired, I went to bed early.”

If they aren’t able to do this, you can try giving longer sentence starter.

Your starter could be the entire clause, like this:

“Because I was tired….”

The goal is to make your sentence starter shorter and shorter, until the students don’t need it anymore.

Since our students will have a difficult time with the order of presentation, you could pair the pictorial support strategy I talked about here by showing a picture that represents each clause like this:

(take a picture of my drawing for the sentence above).

The last challenge is to get your students to use an adverb.

There’s a chance that our students might use one if we don’t make an effort to facilitate it (for example they may say: “Because I was tired, I went to bed.”).

If that’s the case, we might need to have a target word we give our students beforehand. For the example above, we might tell the students that we’re going to help them make a sentence that we want them to use the word “early” in their sentence.

This goes without saying, but give your student a lot of examples and models before you ask them to try the task.

This brings us to the end of the third installment, so let’s recap those goals one more time (I’m narrowing it to the ones I’d recommend in most cases):

Don’t forget to check out Syntax Strategies for Speech Therapy Part 1 and Syntax Strategies for Speech Therapy Part 2: Using Passive Voice if you haven’t read them yet.

To get a complete guide on the most important syntactic skills and how to treat them, download this free guide for SLPs.

This free guide is called The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure.

Inside you’ll learn exactly how to focus your language therapy. Including:

- The hidden culprit behind unexplained “processing problems” that’s often overlooked.

- The deceptively simple way to write language goals; so you’re not spending hours on paperwork (goal bank included).

- The 4 sentence types often behind comprehension and expression issues and why they’re so difficult.

- An easy-to-implement “low-prep” strategy proven to boost sentence structure, comprehension, and written language (conjunctions flashcards included).

References:

Erickson, B. (2017). Unraveling difficult sentences, part 2 of 4 series: The adverbial clause. Retrieved July 13, 2017, from http://www.ericksoneducationalconsulting.com/blog/unraveling-difficult-sentences-part-2-of-4-series-the-adverbial-clause