Welcome to the fourth installment of the Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy, where I’m breaking down difficult sentence types so you can walk away with an IEP goal bank for syntax and a set of solid syntax activities for speech therapy.

The inspiration to write this series came from the constant questions I get about how to write good, measurable goals in speech therapy we can actually track. Then, when I heard about Zipoli’s (2017) article in this post by Tatyana Elleseff from Smart Speech Therapy, I knew I had to dig in to this a bit further.

So far we’ve talked about our base behavior, which is the first step in writing a solid IEP goal that you can actually track. I covered that in the first article in the series.

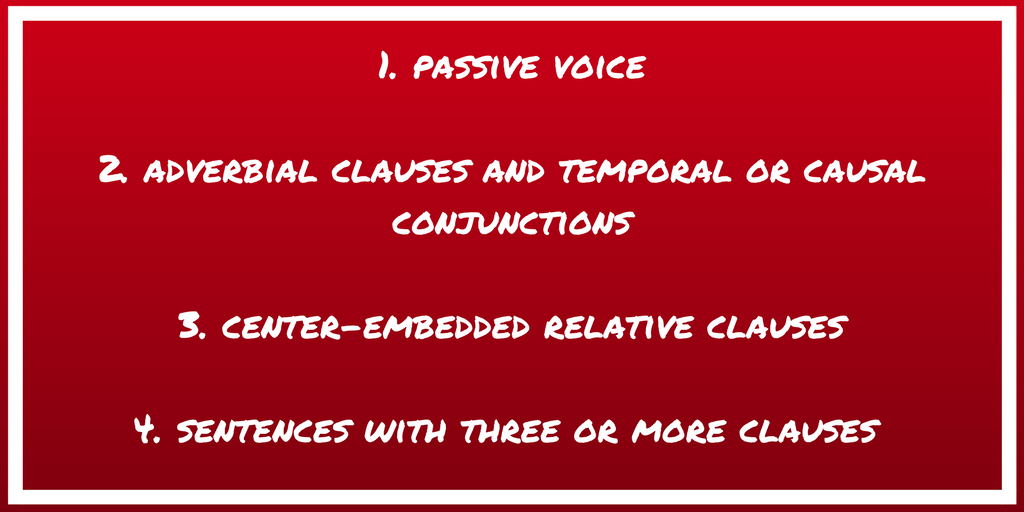

In the second and third parts of this series, I talked about writing IEP goals when you’re working on sentences with passive voice and sentences with adverbial clauses and temporal/causal conjunctions.

These two sentence types are often a struggle for students with language issues; and can often be the culprit behind language processing issues (Paul & Norbury, 2012).

When we have students with disorganized language whose sentences “sound funny”, but we aren’t quite sure what to teach them, one key area we can target is syntax. When we know the root of the problem, we can effectively plan effective syntax activities for speech therapy.

Zipoli (2017) gave us a roadmap to by highlighting four difficult structures. They are:

Now I’ll get to sentences type #3:

“Sentences with center embedded relative clauses.”

Before we go any further, let’s define some key terms so we know how to work them in to syntax activities for speech therapy.

A relative clause is a phrase that acts as an adjective. It’s a dependent clause, and it usually starts with relative pronouns such as “that”, “who”, or “which”.

If a relative clause is “center-embedded”, it means that it’s placed in the middle of an independent clause. This distinction is important, because the order of words is often difficult to process for our students.

The fact that this type of clause happens in the middle of an independent clause requires us to hold certain pieces of information in our working memory and refer back to them later, which is a struggle for students with language processing issues.

Let’s look at a couple examples so you can see what I mean.

“The boy who was sick went to the doctor.”

The relative clause here is “who was sick.” This functions like an adjective because it’s describing a noun (the boy).

It’s embedded in the center of an independent clause that could stand alone as a sentence (“The boy went to the doctor.”).

Before we go on to another example, let’s think about why this might be difficult to process.

First we hear “the boy”. The main idea in the sentence is that he went to the doctor. “The doctor” is the receiver of the action in the independent clause.

The tricky part is that we’ve got the relative clause that essentially interrupts the message to let us know that he was sick when he went to the doctor.

This “interruption” can be difficult for students with language processing issues because of they rely on word order and order of mention.

Let’s think about what might happen when you’re completing some syntax activities for speech therapy.

If we were to ask a student with a processing difficulty what the boy did, they may just say something vague about him being sick, because that’s what they heard immediately after “the boy”.

Or, if we ask them why the boy went to the doctor, they might not be able to infer that he went probably went because he was sick.

Last, what if we ask who was sick?

When you hear the relative clause “who was sick”, you need to be able to refer back to the noun. This requires considerable working memory skills…skills that our students may not have. They might not be able to answer this question accurately.

Before we move on to the goals, let’s go through a couple more examples of this sentence type.

“The new puppy that lives next door was barking at the children.”

The independent clause here is: “The new puppy was barking at the children.”

The relative clause that describes the agent (the puppy) is: “that lives next door”

Here’s another example:

“The girl who forgot her homework asked the boy for a pencil.”

The independent clause: “The girl asked the boy for a pencil.”

The relative clause: “who forgot her homework”

Now that we’ve gone through the basics, let’s talk about how we might write this in to a syntax goal so you can plan appropriate syntax activities for speech therapy.

I will admit that I have never written a specific IEP goal for this sentence type. If you have global issues with syntax, your students could likely use some work on some of the goals I’ve already given you for your IEP goal bank for syntax.

Many of the goals I’ve already mentioned may be appropriate for your students. When planning syntax activities for speech therapy, we can often tie them back to any goal that requires your students to pay closer attention to word order. This could result in carryover to relative clauses.

But as they say, “Never say never.” There may be times, especially with students who are getting in to later elementary/early secondary school, when you might want to target these more sophisticated sentence types with relative clauses within syntax activities for speech therapy.

Especially if you’ve already addressed some other syntactic skills, and your students still struggle to process and use sentences with embedded relative clauses.

Like the other sentence types I’ve mentioned (i.e., sentences with passive voice, sentences with adverbial clauses with temporal or causal conjunctions), you could target this skill under this broad goal for syntax:

“Student will say/write sentences with correct syntax on 4/5 trials.”

You could target comprehension with this goal:

“Student will answer questions about sentences on 4/5 trials.”

With these two basic goals, you would be covered. Yet if you wanted to make it more specific so that it’s clear what sentence type you’re addressing, you could do that like this:

“Student will use grade level vocabulary in sentences with correct grammar/syntax on 4/5 trials.”

“Student will say/write complex sentences with temporal/causal conjunctions on 4/5 trials.”

Now let’s move on to your therapy strategy for syntax. It’s called “sentence decomposition.”

When you complete sentence decomposition, you are breaking sentences apart in to segments to help students see and understand all of the parts (Zipoli, 2017).

You are essentially doing for your students what I did for you when I was explaining this sentence type.

What you may do is start with a sentence like this:

“The girl who was tired went to bed.”

Then you can practice taking the sentence apart, showing your students that you can take out the words “who was tired” and still have a complete sentence.

After that, you can put the sentence back together.

You can also try doing this in reverse to get your students to use this type of sentence, which is more of a sentence combining technique (and also one of the most powerful syntax activities for speech therapy).

This may involve giving your students several shorter sentences or clauses (either auditorally or in writing) and see if they can combine them in to one sentence.

You can incorporate pictures here to facilitate sentences as well. For example, if you show your students a picture of a girl who appears to be tired, you might spend a quick minute talking about the girl, how she is tired, and what she might do because of it.

Then you might want to write out parts of the sentence as you’re discussing the picture or situation, like this:

“who was tired”

“went to bed”

After that you would have students see if they can create a sentence using those sentence parts, like this:

“The girl who was tired went to bed.”

Repeated modeling and practice here is key. Your students may need to hear you say it many times before they are able to catch on.

You can play around with this and see how much of the sentence you need to write out for your students. We would hope that eventually they would be able to come up with sentences on their own, without you having to write parts of it, but we may need to work up to it.

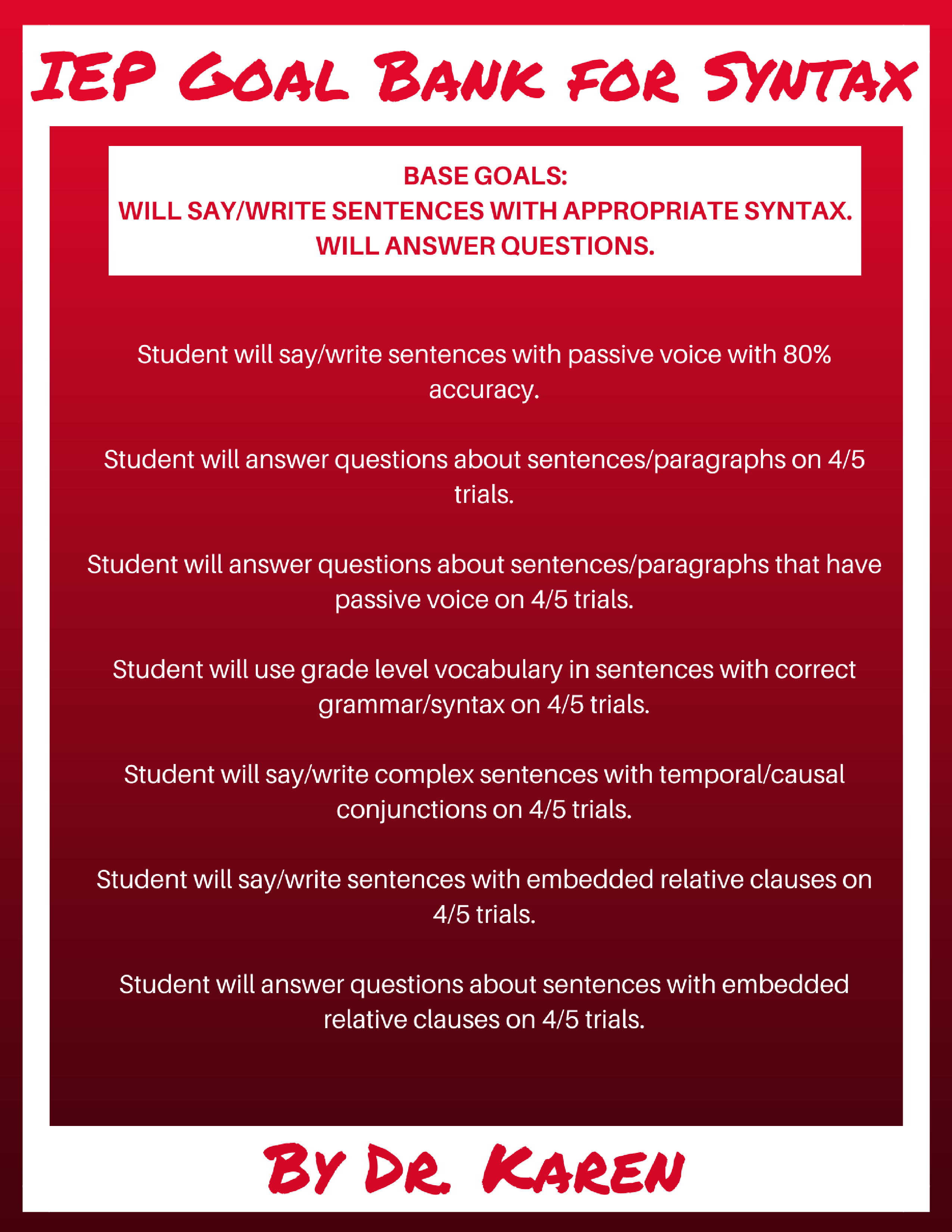

As we wrap up this fourth articles in the Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy series, let’s update that IEP goal bank:

This leaves us with one more sentence type (sentences with three or more clauses) to cover, so stay tuned for the next article.

To get a complete guide on the most important syntactic skills and how to write goals and treat them, download this free guide for SLPs.

This free guide is called The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure.

Inside you’ll learn exactly how to focus your language therapy. Including:

- The hidden culprit behind unexplained “processing problems” that’s often overlooked.

- The deceptively simple way to write language goals; so you’re not spending hours on paperwork (goal bank included).

- The 4 sentence types often behind comprehension and expression issues and why they’re so difficult.

- An easy-to-implement “low-prep” strategy proven to boost sentence structure, comprehension, and written language (conjunctions flashcards included).

References:

Erickson, B. (2017). Part 3 of 4 series: Focus on the center-embedded relative clause. Retrieved July 13, 2017, from http://www.ericksoneducationalconsulting.com/blog/part-3-of-4-series-focus-on-the-center-embedded-relative-clause

Wallach, G. P., & Miller, L. (1988). Language intervention and academic success. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.