Before we dive in to our second installment of Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy and add to that IEP goal bank I started for you, I’ve got a question for you.

How many times have you gotten the dreaded language processing referral?

It might go a little something like this:

Teacher: My student sounds funny. I can’t understand what they’re saying half the time. She’s clueless and doesn’t know what’s going on in my class.

SLP: Can you be more specific? What exactly is hard for them?

Teacher: I don’t know. She just doesn’t sound right. Something isn’t clicking. Can you just come in and check it out?

This is a fair enough statement on the teacher’s part. After all, that’s why you’re here.

So you, the SLP, proceed to go observe or screen the student. You pray that you’ll be able to give some helpful advice.

Yet you come back from your screening or observation just as confused as the teacher. The kid “sounds funny”, something “isn’t right”, and things just aren’t “sticking.”

What gives?

Well, with a language processing issue, it could be a number of things.

But one thing you should always consider is syntax.

While I can’t guarantee that this is always the #1 culprit, I can say that this is one severely overlooked area.

Its not that we don’t know syntax is a problem. Its because we’re not sure where to start, or how to write syntax goals for speech therapy (no matter how many IEP goal banks we consult).

Thankfully, Zipoli (2017) has given us a roadmap of sorts with his article in Intervention in School and Clinic, where he pinpointed four sentence types that are difficult for students with language disorders.

In this post, I’ll be deconstructing the first one of them so you’ll walk away with a couple more syntax objectives for your IEP goal bank.

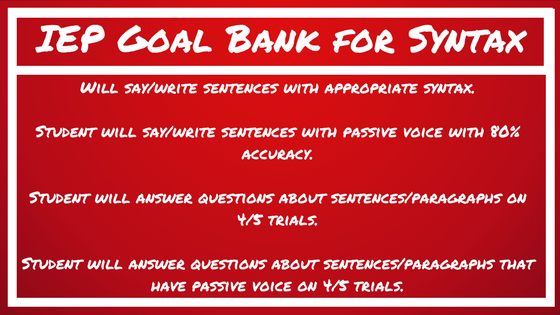

First, let’s review the IEP goal bank as it sits now, with one base goal:

“Student will write/say sentences.”

In the first article in the series, I also talked about my preference for keeping my goals as efficient as possible.

This is why any IEP goal bank I create will have a few goals that combine the oral and written in to one goal.

Whether or not you decide to separate oral from written depends on a number of things:

Is another person is targeting syntax?

If a special education teacher has written a goal for syntax in essays, I may only write my goal for oral language. If not, I may include both oral/written.

How many other language goals does the student have?

If this is a kid who needs help with EVERYTHING, I’ll keep this syntax goal as efficient as possible. I will write more general goals so that I can cover more linguistic elements (e.g., semantics, syntax, morphology). If I dive too deep, I’ll end up with a million goals I’ll never be able to track.

Is syntax the main area of struggle?

If it is, then I might want to put other language skills on hold for the time being and make my IEP goals dive deeper in to specific syntactic skills. When we know that there is one heavy hitter that’s holding our students back, our time might be well spent breaking one linguistic component in to specific skills (in this case, syntax).

So, even though I like goals to be efficient, I still think its advantageous to have some specific syntactic structures outlined in any IEP goal bank for speech therapy (which is why we’ll be adding a passive voice objective to the IEP goal bank in this article).

Passive Voice: What it is and why it’s hard for our students

The first problem sentence type for students with language disorders according to Zipoli (2017) are sentences with passive verbs, or passive voice.

(I will go back and forth between the terms “passive voice” and “passive verbs”).

A sentence has a passive voice when the agent, or doer of an action, and the recipient of that action are reversed (Zipoli, 2017).

The easiest way to deconstruct passive voice is to look at another, less complex type of sentence: sentences with active voice.

When we use active voice, the “doer” of an action (or the agent) comes before the receiver of the action.

This is relatively easy to process because the word order is logical and in a sequence we’d expect.

Here are some examples of sentences active voice:

“The boy threw the ball.”

“The students completed the assignment.”

In both sentences, we hear the agent first (“boy”, “students”). Then we hear what they did (“threw”, “completed”) and to what (“ball”, “assignment”).

Students with language processing issues are heavily reliant on this order. This type of sentence allows them to process one thing at a time, and doesn’t require them to retain and transpose a significant amount of information in their heads (this will make more sense in a minute).

This difficulty with word order is critical to our ability effectively create a good IEP goal bank for syntax, because it can help us understand what language we need to use when defining our observable behaviors.

Now, let’s talk about passive voice.

I can take the sentences I just gave you in the active voice example and change them to use passive voice:

“The ball was thrown by the boy.”

“The assignment was completed by the students.”

In these two sentences, we hear the receiver of the action first (“ball”, “assignment”), even though we may be expecting the “doer”(the boy) to come first.

In order to process this sentence effectively, we need to hold the receiver in our short-term memory long enough to hear the agent. Then we need to transpose the order of the agent/action/receiver and make sense of it.

This also requires taking note of words like “was” and “by the”, which are necessary in order to make passive voice make sense.

Our students are overly reliant on word order because they are often hanging on by a thread trying to remember it all (Owens, 2006; Scott, 2009).

Asking them to think about subtle cues like connecting words, or asking that they retain information and reorder it mentally are a lot to ask.

Yet written language is loaded with passive voice, which means that our students need to be able to recognize, process, and possibly use it.

So…what’s an SLP to do?

Adding passive voice to your IEP goal bank.

Our base goal was “Student will say/write sentences.” The rest of our IEP goal bank will have some variations of this same goal that will make it more specific.

I’m going to keep oral and written combined, but know you can make the decision about whether or not to separate that.

One way to help your students understand passive voice is to have them work on using it. Since that’s the case, we could go with this goal:

“Student will say/write sentences that have passive voice with 80% accuracy.”

See how easy that was? All we did was add this clause at the end of the base goal: “that have passive voice”

Now you’re the one getting a syntax lesson. 🙂

Since syntax is correlated with listening and reading comprehension, we don’t want to stop here.

We also want to consider whether or not our students are understanding syntax.

Here’s what you should NOT add to the IEP goal bank: “Student will understand sentences with passive voice. ”

I’d advise against this goal, because you can’t observe someone “understanding.” Same goes for verbs like “comprehend” or “process.”

Instead, you want to define an observable behavior that shows us that they’re understanding.

One of my go-to “understanding” base behaviors in my current IEP goal bank is: “Student will answer questions.”

Think about it. How do you know if someone understood you? You can ask them a question about what you said.

Truth be told, I would probably keep this goal general and say something like:

“Student will answer questions about sentences with 80% accuracy.”

Or, to make it a little more challenging:

“Student will answer questions about short paragraphs (3-4 sentences) with 80% accuracy.”

Then, what I would do is make sure I was targeting a number of different types of sentences within that ONE goal.

With students who have syntactic issues, there are often so many we could drive ourselves crazy writing goals for every single one. If that’s the case, keep the goal general and just be mindful of the types of skills you introduce within that goal.

On the other hand, I WOULD recommend writing specific sentence types if there are clear problems with specific structure.

For example, if you absolutely feel that your student needs an individual goal for “understanding” of passive voice, it could look like this:

“Student will answer questions about sentences with passive voice with 80% accuracy.”

Easy peasy, right?

Teaching your students to understand and use passive voice.

Time for the fun part. Now that we’ve beefed up our IEP goal bank a bit, what the heck are we supposed to do in therapy?

One deceptively simple technique Zipoli (2017) recommends is called “pictorial support”.

To use pictorial support to target active vs. passive voice, provide a visual of the agent, action, and receiver and show your students how you can rearrange your sentence in order to explain what’s happening.

This is particularly helpful for targeting active vs. passive voice because it gives students a visual representation of the language.

If we don’t incorporate a visual, hearing the sentence aloud may not be enough. If our students didn’t get it the first time, there’s not much we can do other than repeat ourselves.

Sometimes repetition is a valid strategy for working memory issues, but other times the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting something different to happen.

A picture, on the other hand, stays put. Your students will be able to see the picture when the auditory signal is long gone, so they will be better able to make sense of that agent/receiver relationship.

You could target syntax in speech therapy with some simple pictures showing actions like this:

It would be ideal; however, if you had separate pictures to show the agent and the receiver so you could rearrange them in a left to right sequences to show the sentence structure.

One way to do this would be to start collecting pictures of “agents” and “receivers”.

For example, you may have pictures of people or animal as your agents, and then various common objects (e.g., books, food, toys, school supplies) for your receivers. This way you’d be able to mix and match them accordingly.

If it were me, because I’m low-maintenance, I may just show up to therapy with a dry erase board and markers. Or a pencil and a piece of paper. Then I might do something like this:

Those target sentences were:

“The boy threw the ball.”

“The ball was thrown by the boy.”

Please try not to get too jealous of my awesome drawing skills.

This brings us to the end of this second installment. Stay tuned for the third article. Let’s sum up some goals and syntax strategies for speech therapy:

If you missed the first installment of Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy, you’ll want to hop over here and read the first article.

To get a complete guide on the most important syntactic skills and how to treat them, download this free guide for SLPs.

This free guide is called The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure.

Inside you’ll learn exactly how to focus your language therapy. Including:

- The hidden culprit behind unexplained “processing problems” that’s often overlooked.

- The deceptively simple way to write language goals; so you’re not spending hours on paperwork (goal bank included).

- The 4 sentence types often behind comprehension and expression issues and why they’re so difficult.

- An easy-to-implement “low-prep” strategy proven to boost sentence structure, comprehension, and written language (conjunctions flashcards included).

References: