Many of us know we should address syntax in speech therapy sessions for kids with language disorders; but many of us aren’t really sure where to start.

I’ve made the mistake of skimming over syntax and going right to comprehension strategies; like with my student John I talked about in this article.

John wasn’t making any progress working on stating the main idea and answering inferencing questions; but I soon realized after I re-evaluated him that I was completely missing the root cause of the problem.

John had significant issues with syntax and grammar and I needed to back up and address those issues before he could benefit from high-level comprehension strategies.

After reading articles like this one by Nippold (2017) or this one by Gillon and Dodd (1995); I finally started to understand what I may have missed in many cases over the years similar to John’s.

Gillon and Dodd (1995) outlined some specific treatment techniques for spoken language that ALSO can improve reading comprehension; which is an important finding because we want to know that what we’re doing in therapy is going to transfer to other tasks.

In their study, Gillon and Dodd listed some specific strategies that therapists can feasibly do in a typical language therapy setting (even in the school systems).

This included things like sentence combining and deconstruction, semantic webbing, or identifying compound and complex sentences.

But if you’re anything like me, you might want a little bit more of an explanation about how to do a couple of these techniques in real life beyond what was described in the published article.

So that’s what I’m going to do for you today. I’m going to dive in to ONE of these techniques and show you a step-by-step protocol for targeting syntax in speech therapy.

That technique is sentence combining.

Sentencing combining can not only improve a student’s oral language skills (Gillon and Dodd, 1995), but it can also improve the length and quality of written language (Saddler, 2005).

For busy SLPs, this approach can be somewhat of a “magic bullet” for addressing syntax in speech therapy. Not only can it can result in carryover to other academic tasks; but it’s also something we can feasible do in a 30-40 minute session each week.

That, and it addresses a skill that most likely no one else is addressing as well as you can; and that might be holding students back from making progress.

There are a number of different ways you can use sentence combining to target syntax in speech therapy. I’m just going to show you how to put two simple sentences together to form a compound sentence using a coordinating conjunction.

This is not the only type of sentence structure you’ll want to address.

You’ll also want to teach students other skills; such as forming compound subjects and verbs, complex sentences, and sentences with embedded clauses; but I’m just going to walk you through one exercises so you have a starting point.

Materials for targeting syntax in speech therapy

I’m going to hop on my soapbox for a minute. What do you REALLY need to do this exercises?

Technically speaking, a pencil and a piece of paper.

If you get good enough at this that you have the activity “in your head”, you’ll be able to whip a good therapy session together without any fancy “materials”.

But, since I know you may want to save some brainpower and have a few things on hand, here are some materials that could come in handy when doing and activity for syntax in speech therapy:

Pencil

Markers

Paper

Dry Erase Board

List of coordinating conjunctions

List of simple sentences

The school supplies list is self-explanatory, but let’s talk a minute about the conjunctions and sentences.

As I said before, you’ll want to move on to more complex sentence types once you’ve gotten the hang of compound sentences (which I address in my course, Language Therapy Advance).

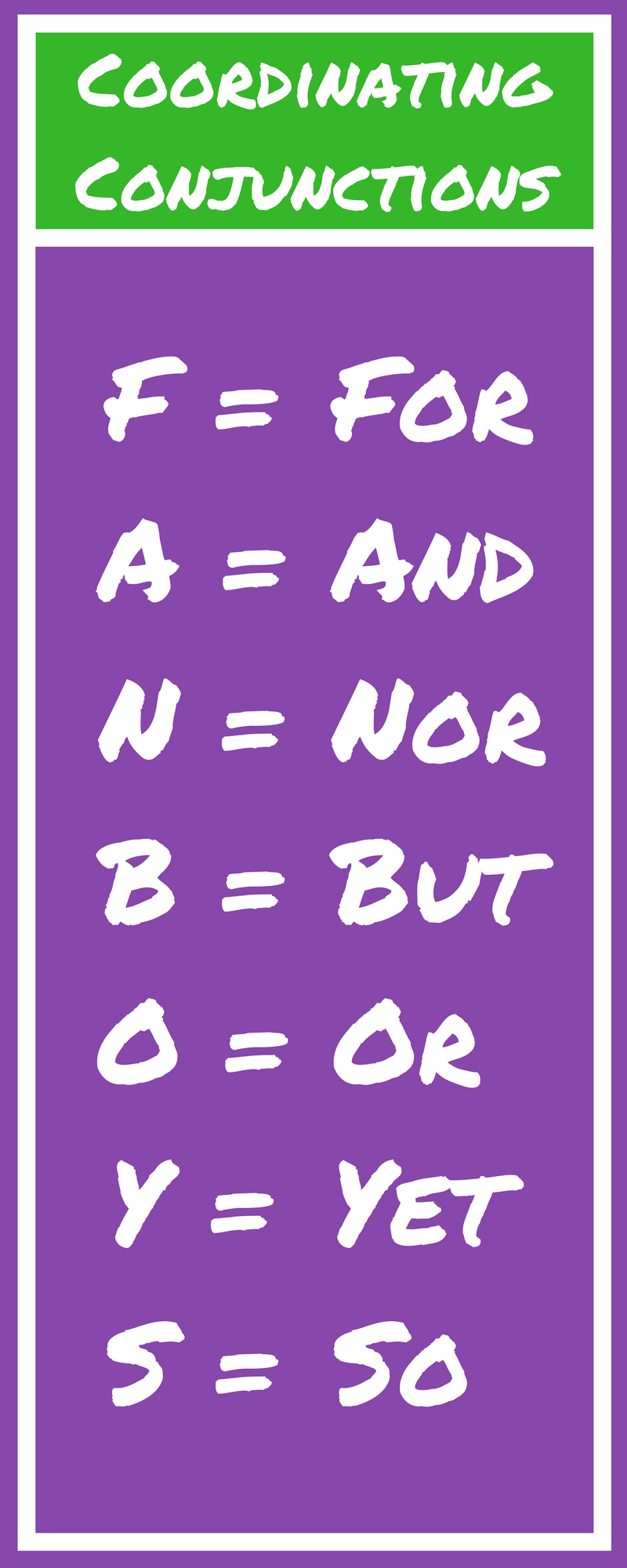

If you’re addressing more advanced sentence types, you’ll also want to use subordinating conjunctions; but to keep this simple we’re just going to stick with coordinating conjunctions for now.

Coordinating conjunctions are considered “cohesive devices” that join words or part of sentences together. In this exercise, you’ll be using a conjunction to combine two simple sentences in to one, longer compound sentence.

You can use the FANBOYS acronym to remember what those coordinating conjunctions are: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So

If you want to start with something easier and gradually make it more difficult, I recommend starting with 1-3 conjunctions at a time.

When I first start doing syntax in speech therapy for most kids, I usually start with “and” and “or” and build from there.

Next, you’ll need a set of simple sentences.

A simple sentence has a subject and a verb and only has one clause. It can have compound subjects or verbs; but focuses on one key idea. A simple sentences is also known as an independent clause because it includes a complete idea and can stand alone as a sentence.

Here are a couple examples that have simple subjects and verbs:

John went to school.

Mary ate lunch at home.

The children played.

Here are a couple simple sentences with compound subjects:

John and Joe went to school.

Mary and Adrian ate lunch at home.

The children and adults played.

Now here they are one more time, this time with compound subjects and verbs:

John and Joe went to school and learned.

Mary and Adrian ate lunch at home and read.

The children and adults played and laughed.

*Notice that a simple subject can still have a plural noun.

This is where it’s important to have things “in your head”. Before your session, you could come up with a list of sentences, or get some worksheets designed for syntax in speech therapy that have lists of simple sentences you can use.

Or, you can do what I do, which is walk in to a session with some dry erase markers and come up with sentences on the fly. It sounds boring, but I let the kids write on the table because it has a glossy finish and the marker comes off easily.

Somehow “breaking the rules” and writing on the table gets them excited. If you have a window you can let them write on that too; or let them draw pictures with their sentences. There are a lot of ways you can make this interesting without a lot of bells and whistles.

Last, even though it’s not in the list of “materials”, let’s talk about compound sentences.

A compound sentence has two independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction.

Here are a couple examples:

John and Joe went to school, and Mary and Adrian ate lunch at home and read.

The children played and laughed, but the adults went to work.

I went to bed early, so I did not have time to finish the book.

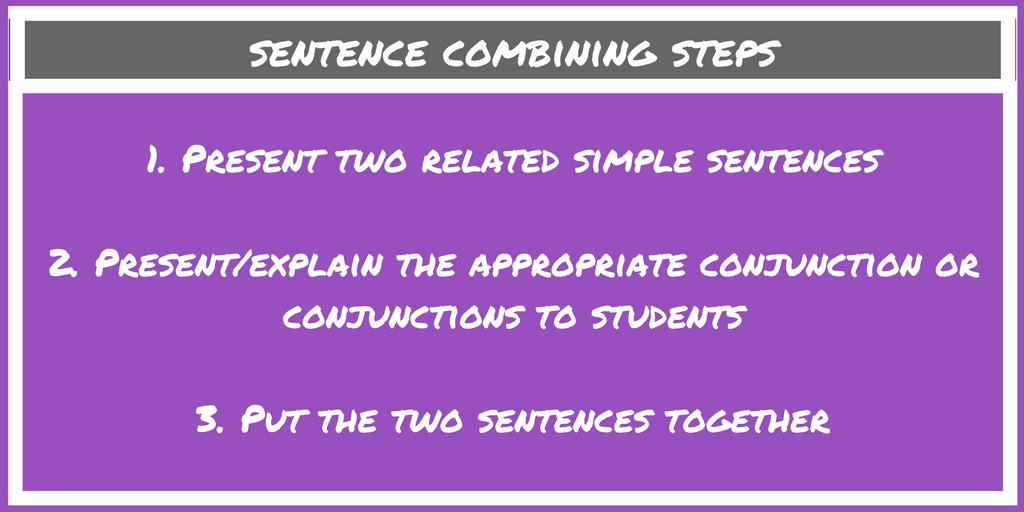

Next, here are the steps:

1. Present two related simple sentences

You can do this however you want, whether it be writing the sentences down so students can see, or giving it to them on a worksheet. The important part here is to make sure that the sentences could logically go together to form one compound sentence.

For example: Allie had dinner at home. John went out to eat.

2. Present/explain the appropriate conjunction or conjunctions to students

This may or may not be necessary once students get the hang of this. At this point you want to write the appropriate coordinating conjunction that the students could use to combine the sentences. For example, you may want to write the word “and”, or “but” in this case.

Then explain that it’s a word for connecting ideas, and I ask them to use the word to create one, longer sentence out of the two simple sentences. Once kids get good at this, you may not need to give them the conjunction. Rather you can just give them the sentences and see if they can come up with an appropriate conjunction on their own.

3. Put the two sentences together

Last, we have the student say or write the sentence. It should go without saying that you may need to model this and walk students through it with assistance before letting them try it on their own.

Throughout this process, I typically use the technical terms with the students, such as “conjunction”, “simple sentence”, and “compound sentences”.

Students are required to know the difference in these terms based on the Common Core Standards by late elementary school; so I want to make sure they have an accurate understanding.

If you’re feeling unsure about how to start working on syntax in speech therapy, forming compound sentences is a good place to start. This can actually get to the root cause of many language issues holding your students back.

To learn a step-by-step process that will lead you through exactly how to build compound and complex sentences, download this free guide for SLPs.

This free guide is called The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure.

Inside you’ll learn exactly how to focus your language therapy. Including:

- The hidden culprit behind unexplained “processing problems” that’s often overlooked.

- The deceptively simple way to write language goals; so you’re not spending hours on paperwork (goal bank included).

- The 4 sentence types often behind comprehension and expression issues and why they’re so difficult.

- An easy-to-implement “low-prep” strategy proven to boost sentence structure, comprehension, and written language (conjunctions flashcards included).

References: