I’ve been hearing some crazy stories from SLPs lately.

The other day, an SLP shared that one of her private clients decided to stop coming because her mom couldn’t afford speech AND dance classes.

So she decided to do JUST the dance classes and drop the speech therapy. Ouch.

Then there was the SLP in one of my programs who shared, “My administrator told me that SLPs shouldn’t be working on vocabulary in speech therapy because that’s a teachers’ job”.

She was at a loss for words.

Then there’s my story. Back in the day, I once had a teacher ask me to help her get her students’ coats on and get them lined up to get on the bus instead of doing therapy sessions.

To say it was a blow to my ego is an understatement.

These three scenarios seem like they have nothing in common. But they all actually stem from the same issue.

…That parent who pulled her child out of speech therapy for dance classes?

…That administrator who said SLPs have no business working on vocabulary?

…The teacher who saw more value in me functioning as a teaching assistant than a therapist?

The problem?

None of them truly understand what an SLP actually does.

And it’s also likely they don’t understand how important our role is in treating language issues; particularly to address important life skills like reading.

The sad part is that situations like this happen all the time. And when they do, it puts a huge damper on our ability to show up and serve our clients fully.

Which is why in this post, I want to give you the information you need to sell the value you provide; specifically as it relates to creating better readers.

What are we currently doing to support reading (and is it working for kids with language disorders)?

A lot of the SLPs who come to me for support know that they play a part in addressing literacy-based issues.

They also realize that the whole purpose of reading is to comprehend (which none of their clients can do very well).

Usually their clients’ parents, teachers, and other caregivers are reporting a slew of symptoms.

This might include problems answering questions and grasping the “main idea” of things. Poor reading comprehension scores. Struggling to follow directions, draw inferences, and retell.

So naturally, because these symptoms all point to weak comprehension, most of my mentees have been focusing on standard “comprehension strategies”.

…They’ve practiced inferential questions til they’re blue in the face.

…They’ve gone through all their “wh” question word decks a million times, and they’ve even taken it a step further and worked on answering “wh” inferencing questions about paragraphs students have read.

…They’ve worked on stating the main idea, but it’s like pulling teeth.

…They’ve even practiced all of those following directions games and had the same “will follow 2-3 step directions with 80% accuracy” goal on their therapy plan for longer than they can remember.

A lot of them are getting frustrated…and even a bit nervous.

If they’re in private practice a lot of them are stressed because their clients’ parents are hounding them about when their child is going to start making progress.

Not to mention the fact that when it comes to supporting students with language issues; they’ve got a lot of competition from other tutors and literacy specialists, since a lot of people don’t even realize an SLP can address language and literacy.

Those who have regular contact with school staff are getting used teachers are still complaining that their kids can’t understand what they’ve read, that their spelling and writing is atrocious, and that they can’t follow along with class directions.

The SLPs in the schools are worried about showing up to the IEP meeting without much progress to report, and they’re starting to wonder if what they do in therapy is just a drop in the bucket.

And then there are the clients themselves.

They’re sick of coming to therapy. They’re tired of being asked over and over again to things that make them feel like a failure.

Feeling “stuck” when it comes to language therapy can cause a slew of issues for SLPs. Losing clients. Being undervalued and underappreciated. Losing your sense of purpose. This list goes on.

So it’s no wonder many SLPs feel overwhelmed and frustrated when it comes to language therapy.

The good news is that if any of these scenarios sounds familiar, it’s still possible to turn it around by focusing on the right things.

But here’s the problem: If you ask 7 different literacy and language experts what SLPs “should” be doing to support language, literacy, and overall language comprehension, you’ll likely get 7 different answers.

If you do a Google, Teachers Pay Teachers, Pinterest, or forum search for “language therapy activities to boost reading” you’ll get hundreds, maybe even thousands of options.

And if you’re a busy clinician who just wants to know what works, you probably don’t have time to sift through all of that.

The problem isn’t that we don’t have enough information floating around out there about how to support reading skills in language therapy.

It’s that we have too much information.

In other words, we need to simplify.

How can we simplify the way we support literacy and still get good results?

The most obvious way place to start in figuring out how to focus our literacy interventions would be to start with what’s known as the “simple view” of reading (Hogan, Sittner, Justice, 2011; Hogan, Adlof, & Alonzo, 2014).

According to the simple view of reading, listening comprehension is a primary factor that impacts our ability to understand what we’ve read.

Higher-level language skills, like the ability to inference and draw upon the “big picture” or main idea also play a part (Hogan et al., 2011; Hogan et al., 2014).

This explains why certain students may have normal reading fluency scores but terrible comprehension.

While reading fluency CAN cause comprehension breakdowns, some kids somehow pull through with a half-way decent fluency score; yet have no clue what they’ve read.

When this happens, it’s highly likely that they’re not understanding what they’ve read because their listening comprehension skills are impaired.

Incidentally, this is also why many students who have “tests read aloud” as an accommodation still struggle to comprehend.

Additionally, there’s the question of how oral language fits in to the mix.

What we know is that that listening comprehension skills and oral language are distinct skills, but they’re correlated (Gray, Catts, Logan, & Pentimonti, 2017).

This means kids who struggle with oral language are likely to struggle with listening comprehension, and vice versa.

And since we’ve established from the “simple view” of reading that listening skills account for reading comprehension abilities, we’d also be able to draw the conclusion that kids with poor oral language skills are likely to struggle with reading as well.

So when it comes to narrowing our focus in therapy, logic would tell us that if oral language is related to listening comprehension…

And listening comprehension contributes to reading comprehension…

Then they way we’d want to build better readers is to spend therapy focusing on oral language and listening comprehension.

Makes sense, right?

Of course. But as always, there’s more to the story.

The simple view of reading: It’s actually pretty complex

One of the biggest challenges SLPs face when building language and literacy skills is figuring out what skills to target, in what sequence, and how to actually get it done in the limited time they have.

The truth is that when it comes to skills like reading comprehension, it’s not a single skill; but rather a compilation of many skills all applied at once (Catts & Kahmi, 2017; Scott, 2009).

Which is why even though it’s helpful to identify oral language, listening comprehension, and higher-level cognitive skills as important factors; we need to dig a little deeper if we’re going to execute an effective therapy plan.

Thankfully Kim (2017) did an in-depth study that expanded on the “simple view” so practitioners can be a better handle on what we’re dealing with when we talk about the skills required for “reading comprehension”.

It’s appropriately titled “Why the Simple View of Reading Is Not Simplistic: Unpacking Component Skills of Reading Using a Direct and Indirect Effect Model of Reading (DIER)”.

For Kim’s study (2017), she did a battery of assessments with 350 English speaking 2nd graders in the southeastern United States; followed by an in-depth analysis to determine relationships between all the variables measured.

Assessments measured working memory, vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, knowledge-based inference (integration of background knowledge with information in the text), perspective taking, comprehension monitoring, listening comprehension, reading comprehension, and word reading.

The goal of the study was to provide a deeper understanding of what factors contribute to reading skills.

Kim also tested an alternative model to add additional clarity regarding what skills truly impact reading.

Results of Kim’s (2017) analysis

In the preliminary analysis, Kim found that higher order cognitive skills like inferencing, theory of mind, and comprehension monitoring, were related to listening and reading comprehension measures.

Vocabulary and grammatical knowledge were also related to listening and reading comprehension.

Yet after the preliminary analysis, Kim did additional investigation to isolate the variables for the purpose of seeing which ones had the greatest impact on listening and reading comprehension.

The point of this analysis was to identify to extent to which each variable contributed to reading (as opposed to lumping them together, which wouldn’t clarify the extent to which each factor contributed).

That’s why Kim continued with more in-depth analyses (which you can see here in the full-text) to dig deeper in to those variables.

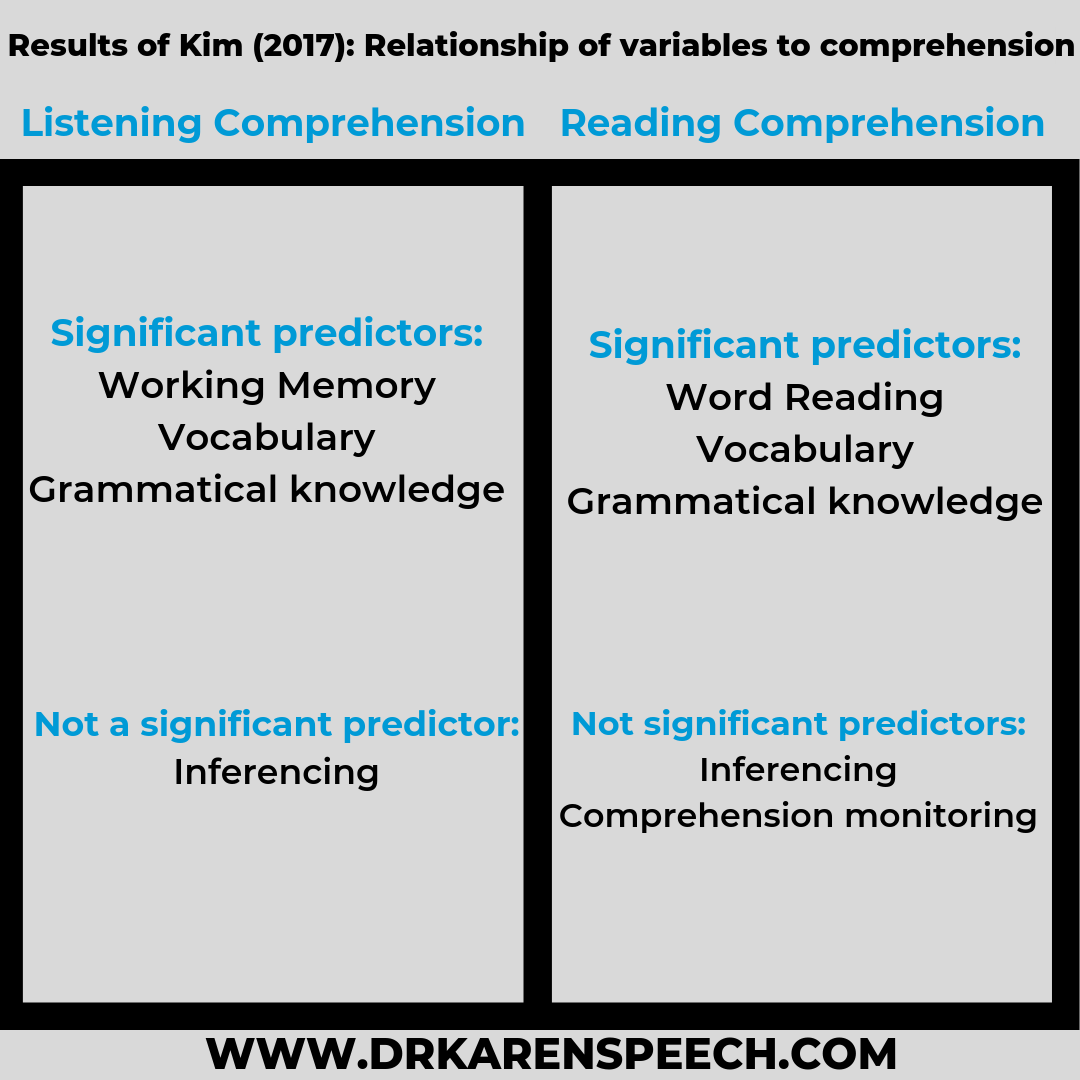

After digging deeper, Kim found that some variables had more significant relationships than others to both listening and reading comprehension. I’ve summed them up in the diagram below:

What factors contributed to listening comprehension?

Some more in-depth analysis highlighted that some factors were more influential than others. Here’s what Kim found:

…Vocabulary was significantly related to inference, theory of mind, and comprehension monitoring when grammatical knowledge and working memory were taken out of the equation.

…Grammatical knowledge was also related to the higher-level cognitive skills of inferencing, theory of mind, and comprehension monitoring when vocabulary and working memory were excluded from the analysis.

…But when accounting for the impact of vocabulary and grammatical knowledge, the relationship between inferencing abilities and listening comprehension was not significant.

What that tells us is that word knowledge is significantly correlated with higher-level cognitive skills.

This tells us that semantic knowledge and understanding of individual words is an important part of the equation.

This also shows is that grammatical skills (which could include things like syntax and morphology) are a key variable that impacts listening comprehension (like I’ve discussed this article here).

Finally, the results indicate that when we look at the impact of each variable in isolation, vocabulary and grammatical skills had strong correlations to listening comprehension skills; while inferencing skills did not.

What factors contributed to reading comprehension?

According to the simple view of reading comprehension (Hogan, et al., 2014), listening comprehension and word reading account for a large portion of our reading comprehension abilities.

Because of this, it should come as no surprise that the analysis of the variables as they relate to reading comprehension are very similar to what Kim (2017) found for listening comprehension.

…Working memory, vocabulary, and grammatical knowledge where all significantly related to reading comprehension.

…Listening comprehension and word reading abilities were also significantly related.

…Inferencing and comprehension monitoring were not.

These findings shows us that underlying foundational language skills like semantic, syntactic, and morphological knowledge account for more of our reading comprehension abilities than our ability to draw inferences or do other comprehension strategies such as stating the main idea.

Perhaps the most obvious finding here is that word reading has an impact on reading comprehension, which is what Nippold (2017) found in her study as well.

This is similar to other sources that have found lexical and topic knowledge to be contributing factors to reading comprehension (McKeown, Beck, Sinatra, & Loxterman, 1992; Rydland, Aukrust, & Fulland, 2012).

These findings indicate that grammatical knowledge is a key variable, which is consistent with other findings that show that morphological analysis impacts comprehension (Vaughn, Roberts, Wexler, Vaughn, Fall, & Schnakenberg, 2015), and that syntactic abilities are a key factor in high-level comprehension (Poulsen & Gravgaard, 2016).

Finally, we need to talk about comprehension and inferencing.

Based on Kim’s (2017) analysis, neither comprehension monitoring or inferencing were significantly related to listening or reading comprehension.

In other words underlying language skills (i.e., vocabulary, grammar) had significant correlations with reading and listening comprehension, while the higher-level cognitive tasks (i.e., inferencing, comprehension monitoring) did not.

This is falls in line with the findings of Nippold (2017), as well as the model outlined by Scott (2009).

Both Nippold (2017) and Scott (2009) suggested that students won’t benefit from “comprehension strategy” work that targets higher-level cognitive tasks if foundational language skills aren’t intact.

What do Kim’s (2017) findings tell us about how to support struggling readers?

Let’s think back to the challenges many of my SLP mentees were experiencing.

Many were focusing primarily on higher-level cognitive tasks and not seeing a significant impact.

Kim’s (2017) analysis sheds some light on why this was happening.

As Nippold (2017) pointed out…even though “comprehension strategies” may be beneficial for the average school-aged student; we can’t assume they’ll work for students who don’t have the underlying language skills to process what they’re reading or hearing.

Those skills that many of my mentees were addressing; such as “wh” questions, comprehension monitoring, stating the main idea, and even drawing inferences…all of these are high-level cognitive tasks that fall under the umbrella of “comprehension strategies”.

It’s likely that many of their clients simply did not have the vocabulary, grammar, and syntactic skills to support those comprehension strategies.

The point to take away is not that we should completely eliminate work on comprehension monitoring, main idea, and inferencing.

Rather, the key takeaway is that we need to ensure our intervention addresses the underlying language skills such as those identified in Kim’s (2017) study (i.e., vocabulary, grammatical knowledge, word reading) to support high-level comprehension.

Which of course means we need to hone in on foundational language skills for a large portion of therapy time to help students become more “meta” aware of how language works.

This way we lay the groundwork so students can actually respond to comprehension strategy instruction.

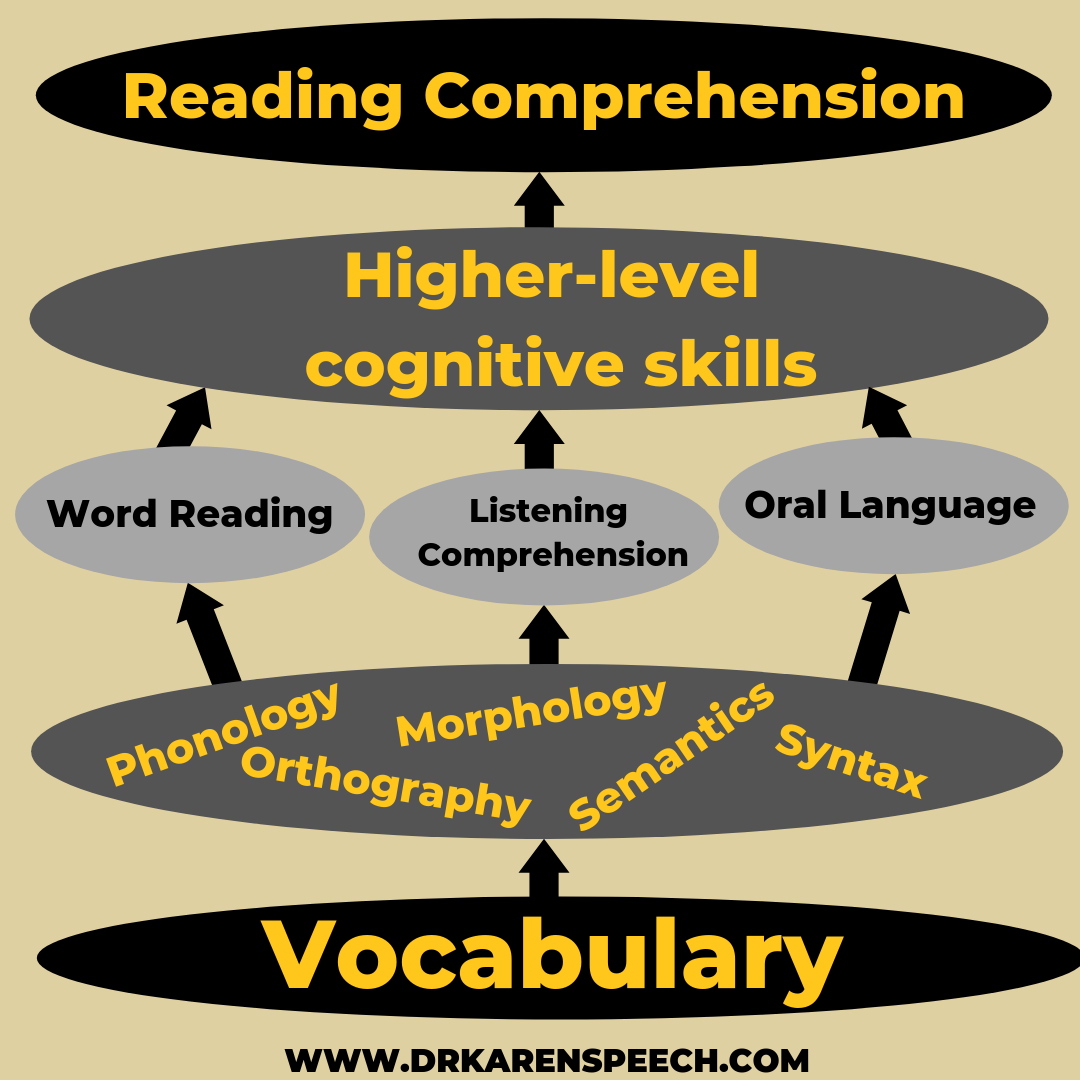

Vocabulary as the starting point for language and literacy intervention for SLPs

In many of my courses and articles, I teach SLPs how to streamline their language therapy by making vocabulary intervention their foundation.

The basic idea is that when we expand our view of what “vocabulary” actually is, we see that it actually includes the other factors highlighted by Kim (2017), such as grammar and word reading; as well as factors needed for reading comprehension identified by Nippold (2017), such as lexical and topic knowledge or syntax.

The first step in the process is strategically selecting target words using, and then we move on to laying the foundation for comprehension by building the 5 “linguistic components” that all impact our vocabulary growth: phonology, orthography, morphology, semantics, and syntax (Kucan, 2012).

Building those foundational skills then makes it possible for students to achieve growth in other areas needed for comprehension; such as word reading, listening comprehension, and oral language.

By solidifying word reading, listening comprehension, and oral language, we make possible for students to perform higher-level cognitive tasks (e.g., inferencing, stating the main idea, comprehension monitoring), which of course results in successful reading comprehension.

I’ve simplified it in the diagram below to show you the high-level view of how this all fits together.

So now, the million dollar question. Where do we start?

When it comes to vocabulary intervention and language therapy, SLPs need to be well-equipped to answer some difficult questions.

There are the clinical questions we ask ourselves, like:

… “Should I even be teaching vocabulary words in therapy?”

… “How on earth can I make time to dig through all of those curricular materials to find vocabulary words?”

… “How do I know how many words I can cover each week?”

… “Is it even possible to get to all the words my students need to know with the limited time I have?”

… “How do I figure out if my clients truly “know” the words I’m teaching them?”

… “Will I ever be able to make a difference when my clients are so far behind?

… “How do I focus on teaching the right words that make a difference?”

And then there are the questions that come from other people we work with.

… “But you’re a speech therapist. What do you have to do with reading? I thought you just fixed the “r” sound.”

… “But this other after-school tutor is way cheaper. Why should I pay more for my child to come to private therapy with you?”

…“But the teachers are the ones who are supposed to be working on vocabulary. How is what you’re doing different?”

In order to be effective and truly serve your clients, you need answers to these questions.

In my signature program, Language Therapy Advance Foundations, I help clinicians find the answers to these types of questions, so they can leverage their expertise and gain more confidence in their clinical skills, and break through therapy plateaus (especially relating to spelling and grammar).

Inside you’ll get a COMPLETE SYSTEM for language therapy designed to help you show up to your language therapy sessions confident.

You can learn more about how to become a member on the enrollment page here.

References:

Kucan, L. (2012). What is important to know about vocabulary? The Reading Teacher, 65, 360366.

doi:10.1002/TRTR.01054

Nippold, M. A. (2017). Reading comprehension issues in adolescents: Addressing underlying language

abilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48, 125-131. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-16-0048

Scott, C. M. (2009). A case for the sentence in reading comprehension. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in

Schools, 40, 184-191. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/08-0042)