One of the biggest challenges we face when working with kids with language disorders is getting them to say longer sentences that clearly communicate their ideas.

Yet expanding sentences our students say is easier said than done, which is why I created this free e-book for SLPs, The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure.

In this free guide, I walk you through the most difficult sentence types that cause language processing issues, plus how to write IEP goals and teach your students these skills.

A lot of my readers have had some follow-up questions after reading through this guide, especially the students studying with me in Language Therapy Advance.

The key to successfully expanding sentences and building vocabulary at the same time lies in these three secrets:

- Secret #1: Syntax and vocabulary are not separate.

- Secret #2: Vocabulary is not just about what words mean. It’s also about what words do.

- Secret #3: Kids can understand more than you think.

Let’s dive in to each one, one at a time.

Secret #1: Syntax and vocabulary are not separate.

In language therapy, we often think of things like grammar and syntax as separate from vocabulary. But that’s not how language works. These separate skillsets interact with each other; it’s virtually impossible to isolate them in to neat little buckets.

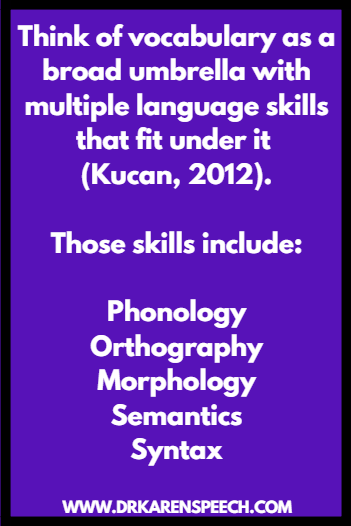

Think of vocabulary as a broad umbrella with multiple language skills that fit under it (Kucan, 2012).

Those skills include:

- Phonology

- Orthography

- Morphology

- Semantics

- Syntax

I’ve explained how they all fit together in this post here.

Today, I’m going to talk about how syntax fits in to this framework.

When it comes to having a well-developed vocabulary, part of “knowing” a word has to do with being able to use it in a sentence with correct syntactic structure (Kucan, 2012; Perfetti, 2007).

The easiest way to explain this first secret is to look at how this might play out in a real-life scenario.

Imagine you’ve spent an entire session studying a word with your student.

You’ve talked about the word’s category, or studied synonyms. You’ve watched videos looking at examples, or maybe shown them pictures.

Maybe you’ve explained it to them using a “kid-friendly” definition.

Then you ask them to use it in a sentence and get one of the three types of responses:

- The “almost but not quite” sentence

- The non-specific sentence

- The avoidant response

Let’s go through each of them one-by-one and talk about why they happen (plus what to do about it when they do).

The “almost but not quite” sentence

This is when a student says a word in a sentence and it’s ALMOST used correctly, but it’s just a little bit off.

For example, pretend you’re studying the word “conclusion”.

Now let’s say you ask your students to use it in a sentence, and they say:

“I’m going to conclusion at the end of my essay to show my opinion.”

What’s going on here?

Well, the student actually confused the word “conclusion” with the word “conclude”.

They know that a conclusion has to do with compiling all the necessary information at the very end of something, but they’re using the wrong form of the word.

In their sentence, they’re using the word “conclusion” like it’s a verb, instead of a noun.

Why is this happening?

To understand this, we have to think about what’s going on during the process of fast mapping.

During fast mapping, we construct meanings of words based on our initial exposures to the words (Perfetti, 2007).

But our initial exposures are often incomplete. That means that haven’t stored all of the semantic and syntactic information about that word right away.

As we have experiences with words over and over again, we fine tune that syntactic and semantic information (Perfetti, 2007). That means we have a better understanding of the meaning of that word (semantics), as well as how to use the word (syntax).

So this means that if we have spent time studying a word with our students, but they can’t use it in a sentence YET, they just haven’t fully fine-tuned their meaning of that word.

This is part of the process and is NORMAL.

If this is happening in your therapy, it DOES NOT mean that your therapy isn’t working.

It simply means you’ve just started laying the foundation.

It’s kind of like how a flower has to grow underground first before it can bloom.

With that in mind, let’s go back to the sentence and figure out how to work through this with our student.

The sentence was: “I’m going to conclusion at the end of my essay to show my opinion.”

Your student actually got PART of the information here.

He/she has applied enough semantic information to give some context, but the syntactic structure is incorrect.

One obvious thing you could do is to see if the student can figure out how to correct it on their own.

If they can’t provide lots of models and examples of what WOULD be appropriate.

Some things you could do here include:

- Show them how to change the word “conclusion” to “conclude”. This would correct the sentence and would add morphology to the discussion.

- Show them how to make a minor change in sentence structure, such as saying “draw a conclusion” or “write a conclusion”.

- Discuss why this sentence is incorrect and rewrite the sentence completely from scratch.

Now that you know how to work through this scenario let’s move on to the next common scenario.

The nonspecific sentence

Let’s go back to that word we were studying: “conclusion”.

In the “almost but not quite” example, the student made a solid attempt at giving us an appropriate sentence.

But that’s not always what you’ll get; especially when you ask a student to say a word that’s brand new to them.

Instead, you many get the “super-generic” sentence, like this:

“I like the conclusion.”

Or this:

“I see the conclusion.”

Or my favorite, something like this:

“The conclusion is nice.”

Gotta love the word “nice”. It’s almost as good as “stuff” and “things”, and it’s usually what we say when we can’t think of anything else.

If you’re getting these types of responses, it’s likely because your students haven’t stored adequate syntactic and semantic information about the word.

So let’s talk about how we can help make these sentences better.

If you get a really generic sentence, your students may need a little more work on the semantic component.

This could be an opportunity to review the meaning of the word that you’re studying, and possible remind them of some semantic information (for example: categories, functions, synonyms, antonyms).

But remember, most language learning is NOT linear.

All of the different components of vocabulary impact each other. So even though it is possible to have a system for language therapy made up of a bunch of different techniques we cycle through, we want to maintain some flexibility.

We also want to remember that language skills are INTERRELATED (Perfetti, 2007). This means that working on one area can impact another.

That means that your work on syntax can have an impact on semantic skills.

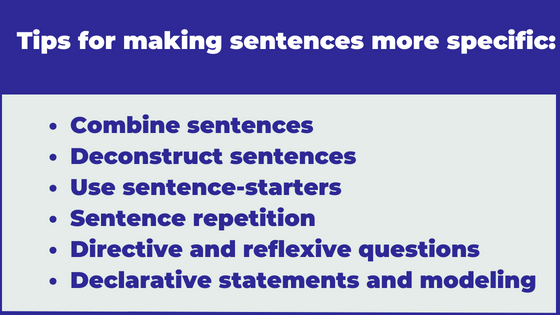

If you decide that you’re going to study syntax with your students, the first step is to decide what sentence type you want to have your student say.

This will help you give more specific feedback instead of just asking your students to “say a word in a sentence”.

In The Ultimate Guide to Sentence Structure, I walk you through some of the most challenging sentence types for students with language disorders to help point you in the right direction.

In addition to those challenging sentence types, you may need to consider some easier sentence types as well. I’ve explained one easier sentence type in this video:

Once you pick the sentence type you want them to use while saying their target word, you’ll want to give them some type of support to help them use the word with that type of sentence.

One possibility would be using a sentence starter, which means that you are saying part of the sentence and letting students finish (Owens, 2016).

Another option would be to do a sentence combining exercise, which I’ve explained in the free guide; where you give the student two sentences they have to combine in to one.

Now let’s move on to the last scenario.

The avoidant response.

The avoidant response is when you ask a student to say a word in a sentence and you can tell by their expression, they’re not sure what to do, but don’t know how to ask for clarification.

Maybe they don’t even respond or even give you a basic sentence. Maybe they stall and even start acting silly.

This happens for a couple reasons:

- Your student is overwhelmed and doesn’t know where to start.

- Your student is delaying getting started because they’re overwhelmed and don’t know where to start.

This happens because of the same reasons I described in the nonspecific sentence, and your plan of action would be the same.

You simply want to scaffold them through the process and gradually fade those prompts to ease the frustration level.

So remember, the first secret is this:

Vocabulary and syntax are NOT separate things. They go hand-in-hand.

Now you have some tools and strategies that will help you use this secret in your practice, it’s time for secret #2.

Secret #2: Vocabulary is not just about what words mean. It’s also about what words do.

I’ve explained under the first secret that when we fast map, we’re attaching syntactic information to our understanding of words (Perfetti, 2007).

And this point is so important that I had to dive deeper in to it for the second secret.

Now that we understand how semantics and syntax relate, let’s talk about how they’re different.

Oftentimes when we think about vocabulary, we go automatically to thinking about semantics because semantics is the study of meaning.

Usually the first thing we think of when “teaching words” is “kid-friendly” definitions, or explaining what word mean.

And this might be true; but if your vocabulary instruction stops here, you’re missing out on a HUGE opportunity to build your students language skills.

The reason I say that is because some words are content words, and some words are function words.

Kids with language disorders have such a difficult time processing certain sentence types; such as sentences with passive voice, or complex sentences (Zipoli, 2017).

The reason these sentence types are difficult is because individuals with language disorders are overly reliant on the word order and the content words in sentences (Paul & Norbury, 2012).

Students with language disorders may pay attention the content words and ignore the function words in a sentence.

Let’s look at some examples.

“The boy was hit by the ball.”

Who was hit? Was it the boy? Or was it the ball?

If you ONLY pay attention to the content words, you’ll think it’s the ball.

But if you also notice the words “was” and “by”, you’ll understand that it was actually the boy.

Here’s another example:

“We went to lunch after we went to recess.”

What did we do first? Go to lunch? Or go to recess?

If you aren’t paying attention to the conjunction “after”, you may misinterpret the message.

Words that would be considered “content” words can include nouns, verbs, and adjectives. These words have a clear meaning and set of semantic features that go along with them.

Function words, on the other hand, can be better explained by what they do rather than what they mean.

One essential type of function word for kids with language disorders is the conjunction.

For example, the word “and” is a function word.

What does “and” do? It connects words, phrases, and clauses because it’s a coordinating conjunction.

I explain what coordinating conjunctions do in this video here (which you can play for your students):

What about subordinate conjunctions? These are extremely tricky for your students; because there are a lot of different pieces of information they convey.

Some subordinating conjunctions explain when things happen, such as words like “after”, “before”, or “during”.

Others explain why things happen, such as “because” or “in order to.”

Then we have words that show conditionality; like “unless” or “if”.

Here’s an example of how to explain that here (which is also something you can play for your students):

Now let’s get to the last secret.

Secret 3: Kids can understand more than you think they can.

One of the most common questions I get when it comes to working on syntax or morphology with students is, “What age group is this appropriate for?”

Again, language growth is NOT linear. As I explained in this article, language development is so variable that it’s virtually impossible to give a nice and neat developmental milestones chart for kids in Kindergarten through 12th grade.

Regardless, I can tell you that we should be working on these more advanced language skills WAY SOONER than we think.

First of all, when it comes to really studying word meanings, research has shown that kids can infer meanings of words based on affixes as early as first grade (Apel & Henbest, 2016). Morphological makeup of words impacts how we use them in sentences, so this finding supports the notion that we can start working on these skills sooner, rather than later.

We also know that without direct work on syntax, kids will continue to struggle with these skills; and they will have an impact on reading comprehension (Nippold, 2017; Scott, 2009). So much, in fact, that kids may not be able to benefit from comprehension strategy instruction if we don’t address issues with sentence-level comprehension.

Second, instruction for kids with language disorders needs to be more explicit than implicit. That means that while many kids may pick up on complex sentence structures from exposure alone, students with language disorders may not.

Many students are using complex sentences in oral language as early as Kindergarten; yet students with language disorders lag behind with this skill in oral and written language (Poirier & Shapiro, 2012).

This is a clear sign that this skill needs time and attention, because issues with syntactic comprehension will persist if we wait until the later grades to address it.

There’s good news though. Our students can learn these skills if we teach them the right way.

I give SLPs and other professionals work on language a system for doing this in Language Therapy Advance Foundations.

Language Therapy Advance Foundations provides a research-based framework for supporting the underlying language skills need for strong comprehension and expression.

If you’re an SLP and you feel like you don’t have a clear hierarchy for language or feel like you’re cobbling lessons together without a clear plan, I get it.

That’s exactly how I felt my first few years as an SLP, and I’ve repeatedly met OTHER experienced SLP who feel like they still don’t have a grasp on language intervention, even after years of practicing.

That’s what inspired me to make language and cognition my area of expertise during my doctoral work, where I created a process that incorporates the 5 components of vocabulary intervention I described in this article (orthography, morphology, phonology, semantics, and syntax).

Learn how to become a Language Therapy Advance Foundations member here.

References:

Apel, K. & Henbest, V. S. (2016). Affix meaning knowledge in first through third grade students. Language Speech and

Hearing Services in Schools, 47, 148-156. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0050

Kucan, L. (2012). What is important to know about vocabulary? The Reading Teacher, 65, 360366.

doi:10.1002/TRTR.01054

Nippold, M. A. (2017). Reading comprehension issues in adolescents: Addressing underlying language

abilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48, 125-131. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-16-0048

Poirier, J., & Shapiro, L. (2012). Linguistic and psycholinguistic foundations. In Peach, R. & Shapiro, L. (Eds.), Cognition

and acquired language disorders: An information processing approach (pp. 121–146). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier

Mosby.

Scott, C. M. (2009). A case for the sentence in reading comprehension. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in

Schools, 40, 184-191. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/08-0042)