There isn’t a week that goes by that the typical pediatric SLP doesn’t wonder how to fix their students’ reading comprehension problems.

The problem is that most people are doing this backwards for kids with language processing issues.

Many are skimming over some of the basic foundational skills our students need to be good readers in the long run.

If you read my last post that highlighted some essential skills that can predict future reading comprehension, you may already know what I mean.

I started to come to this realization when I struggled to diagnose problems with my student John, who had reading comprehension problems and behavioral issues that may stemmed from issues with poor grammar and syntax.

After making little progress with the high level comprehension work, I realized I needed to back up and work on some of the things I’m going to share with you today based on a longitudinal study by Nippold (2017).

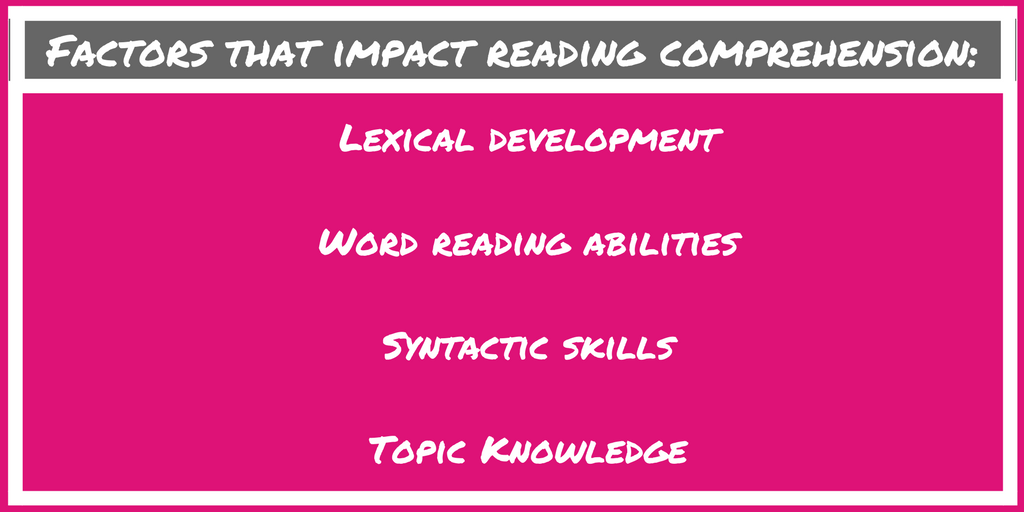

Nippold found that there were 4 key areas that impact reading comprehension. Let’s talk about each one and why it might be holding our students back.

Lexical Development

Vocabulary is a huge predictor of later reading comprehension problems. Lexical knowledge, often known as “word knowledge”, is needed in order to make sense of what we’re reading. In order for paragraphs to make sense to us, we need to understand the words in the sentences we’re reading.

We also need to be able to know enough of the words in the passage to infer meanings of unfamiliar words when we come across them. This is a pretty powerful strategy; because it helps us learn NEW words independently.

This might include using strategies like context clue analysis; where we read the surrounding sentences and use that information to figure out what the word might mean.

It also might include morphological analysis; which involves looking inside the word’s parts to infer what the word might mean based on the prefixes, suffixes, bases, or roots.

For example, we might be able to determine that the word “redesign” means “to create something again”, because we know that “re” means “again” and “design” means “to make or create.”

If a student has issues grasping new vocabulary words, they may need specific instruction focused on strategies that will help them learn new words.

Yet many times we work on reading comprehension by asking a student to read something and ask them a set of general questions, like “What happened?” and “Why did X happen?”

While these types of questions may cue students to actively think about what they’ve just read, they may not be specific enough if the student lacks lexical knowledge or the ability to use strategies to infer new word meanings.

Word Reading Skills

This one is often referred to as “decoding”. By the time children reach adolescence, they need to do the following in a rapid manner in order to read efficiently:

Apply phonological awareness and letter/sound knowledge

Apply morphological awareness to read morphologically complex words

For example, in the word “big”, we don’t have to sit and think about what sounds are represented by each letter. Instead, we perceive the word automatically, because our phonological awareness and letter/sound knowledge is intact to the extent that it doesn’t require significant cognitive resources. This is also true for words that have phonics patterns that don’t have a 1:1 correspondence between letters and sounds.

For example, words like “could”, “should”, or “would” all have “oul” that represents the same vowel; which we recognize as a consistent pattern and will be able to remember when we pronounce those words.

When we perceive morphemes, we need phonological knowledge to know how to pronounce the morphemes.

For example, we know that the prefix “pre” has three separate sounds. We also know how to pronounce grammatical morphemes like “s”, or “ed”, and we know that the pronunciation for those morphemes varies depending on the root or base word (all of which have consistent, logical patterns).

As we become more familiar with these word parts, we don’t have to “sound words out” one sound at a time; rather we see the word parts and read them quickly. Again, which allows us to have energy left over to actually comprehend what we’re reading.

But our students with language impairments are likely to struggle with phonological and morphological awareness; which means they’re also likely to have reading comprehension problems.

If we don’t explicitly target phonology and morphology, decoding is not likely to improve; which means some students may not have the word reading skills to be able to benefit from “comprehension strategies.”

Syntactic Skills

Let’s go back and talk about my student, John. In conversation, he was able to hide his syntactic difficulties by avoiding the hard questions and by answering in short sentences.

But when he was pushed, we found that he didn’t have a complete grasp on complex sentence structures; which was causing reading comprehension problems.

The fact is, many academic reading passages (or verbal discussions for that matter) have sentences that are long and complex. The structure of sentences in texts gives us insight as to what information is and isn’t important.

My student John, had significant difficulty distinguishing between what was the “main idea”, was a “supporting detail”, and what was completely irrelevant. Which meant he either gave one word responses, or he gave long, rambling answers that may or may not have had the answer buried somewhere in there.

Yet while we worked on “main idea” and “supporting details” until we were blue in the face; we weren’t making progress because I hadn’t addressed his weak syntactic knowledge.

This was why I needed to back up and target sentence structure in order to have an impact on John’s reading comprehension problems. One plan of action for John was to target the four different types of sentence structures that are difficult for students with language impairments (Zipoli, 2017).

That includes: sentences with passive voice, adverbial clauses and temporal or causal conjunctions, center-embedded relative clauses, and three or more clauses.

I talked about the four types of sentence structures in an article series where I outlined syntax goals for speech therapy.

Topic Knowledge

This last one is closely tied to lexical knowledge, but instead had to do with the broad topic of the reading passage and how all of the individual concepts relate back to each other.

Here is where a Catch-22 happens. Students who don’t read well know about fewer topics because they don’t read about them. They avoid reading because it’s exhausting and difficult for them; so they aren’t doing the very thing that will improve their situation.

This is why we need to build a strong foundation of lexical and syntactic knowledge; so we can build the skills that make reading less taxing and more enjoyable. I won’t dive as deep in to topic knowledge and reading comprehension problems because I’ve already discussed lexical knowledge in depth; but know that this last factor ties everything together for our students.

When we give our students a strong vocabulary foundation with emphasis on grammar and syntax, we can set them on the right path.

This brings me to another question about the SLP’s role in remediating reading comprehension problems:

If we target spoken language (which language therapy often does), will that actually improve a students’ reading comprehension?

The question comes up so much because we often feel so much pressure to work on “speech”. While we should be integrating print in our therapy to build orthographic knowledge; there are many cases when language therapy focuses more on oral language.

This is the case because although improving reading skills is a HUGE part of what SLPs do, it’s not the only thing.

We need to build our students’ spoken language so our students can function well in situations that don’t involve print.

It comes down to this feeling of insecurity we all wonder (but don’t want to admit):

Is what I’m doing in therapy really making ANY difference?

Especially if we’ve been highly focused on spoken language instead of doing activities that mimic the classroom setting directly.

If you’ve ever wondered this, there’s good news: It DOES make a difference.

What you do for your students’ “speech” matters; and there’s research to prove it.

I’m going to outline it for you in the next article, where I’ll review a study done by Gillon & Dodd (1995) that looked at the impact of therapy focused on spoken language. In may be an older study; but the findings still hold true.

You’ll see that your work as the “speech” teacher is more powerful than you think.

If you liked this article and want more like it delivered straight to your inbox, sign up for my mailing list here. You’ll also get a set of free Tier 2 Words flashcards that will help you start building the skills your students need to build strong comprehension.

References: