As a professional field, we’re getting stuck in old ways of thinking when it comes to designing services for students experiencing executive dysfunction.

When we think of “therapy” the first thing that comes to mind is a clinician sitting in a chair saying things like, “And how does that make you feel?” or a clinician doing exercises in a 1:1 or group setting.

When we think of “planning for therapy”, we think of what materials or activities we’re going to do with in our direct therapy sessions.

With “social skills intervention”, we think of an adult teaching a group of kids how to follow the rules in social situations, while students answer questions and discuss to demonstrate their understanding.

Lack of generalization continues to be one of the biggest pain points for therapists using these models.

And while most clinicians agree that collaboration with other professionals and caregivers is important, the “planning” for those activities is often less intentional than the way we plan for direct intervention.

That’s why in the School of Clinical Leadership, the first thing I teach clinicians is how to create a long-term strategic plan for putting executive functioning support in place for their caseloads (and sometimes the entire school) using multiple service delivery models.

When the entire intervention starts and ends within a traditional therapy session, students don’t generalize executive functioning skills across settings.

We as a field need to evolve in the way we think about what’s included in “therapy” services for executive functioning.

There are three paradigm shifts clinicians, educators, and school leaders can make when thinking about supporting kids executive functioning in schools.

Shift 1: Planning for Service Delivery vs. Planning for Therapy

One of the biggest challenges therapists have when it comes to executive functioning is generalization. Clinicians also often express that they see poor generalization with “pragmatic language” or “social skills”.

The first distinction that clinicians can make is thinking of “pragmatic language” under the umbrella of executive functioning.

Successful application of “pragmatic language” requires someone to read a room and infer the thoughts, feelings, and perspectives in varying situations. This extends beyond casual socializing, because we can apply this to academic or vocational situations where you’d need to work with others.

When we think of pragmatic language as part of executive functioning, it becomes even more obvious why these skills can’t be addressed with a “pull-out” therapy model alone.

It’s therefore important for clinicians to shift from “therapy planning” to “service delivery planning”.

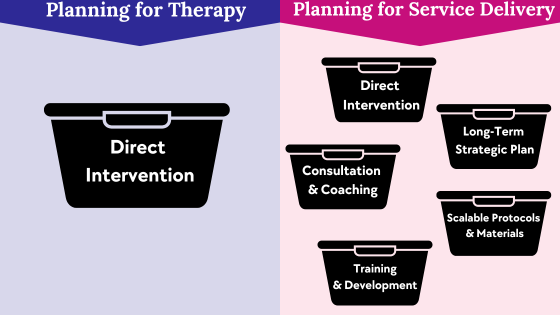

I like to use “buckets” as an analogy for explaining the difference between “service delivery planning” and traditional “lesson/session planning”.

When we think about therapy services, the “model” is like a bucket we can fill with things (materials, strategies, protocols, etc.).

We’d give that bucket a label with the right amount of flexibility and specificity that it could help us organize what we need to do to deliver services. Planning for direct intervention is one of those buckets because it’s one service delivering model.

Repeatedly, I see clinicians putting lots of things inside their “pull-out therapy” or “direct intervention” bucket. This includes things that can be delivered in a group therapy setting, in a “lesson”, or in a 1:1 format.

We need to have quality things in the direct intervention bucket. In fact, there are some skills that specifically need to be in this bucket in order for kids to get the intensity that they need with certain tasks and skills, as I explain in this post here.

But this isn’t the only bucket we need to fill.

We also need to fill the “consultation/coaching” bucket, the “training” bucket, the “protocols and materials” bucket, and the “long-term strategic planning” bucket. There are more we could include, but these are the big ones.

This means instead of just filling the “direct intervention” bucket with more therapy materials, we can create protocols for having a consultation or coaching session with a teacher.

We could be documenting our therapy techniques by creating sharable resources to give to other professionals or parents so they can implement strategies outside our sessions.

We can work with our leadership or adjacent team members on a long-term plan for how we’re going to block out time for all of these things over the course of the next year.

Even if direct therapy looks like the biggest bucket based on the time blocks in your daily schedule, you can (and should) fill the other buckets.

When we plan intentionally for how we’re going to deliver these other models for students, this is what I mean by “planning for service delivery”.

It’s macro level, strategic, and focused on what’s happening across a students’ day, instead of just one time block on your schedule.

Shift 2: Front-loading and Reviewing vs. Siloed Social Skills Groups

One of the largest pendulum swings I’ve seen relating to K-12 education is the discussion about social skills groups.

Are they ableist? Are they educationally relevant? Do they work?

My answer to those questions is “No”, “Yes”, and “It depends”.

We have to equip students with the skills they need to interact with others. This is not a neurotypical skill, it’s a human skill.

Regardless of whether you’re interacting with a neurotypical or neurodivergent person, there needs to be a give and take in the relationship, and all parties need to consider how their behavior impacts others or how they’re coming across. This is important for self-advocacy, independent functioning, as well as maintaining healthy relationships.

When done correctly, social skills intervention (or more accurately, intervention focused on executive functioning for social interactions) can give kids the skills they need to navigate the nuances of human relationships.

Assuming they won’t be able to learn these skills is not only ableist, but also puts them in a very vulnerable situation, as I explain in this post.

Kids also need to interact with peers and adults throughout their school day, so these skills are academically relevant.

But the last question is a common point of confusion: “Do social skills groups work?”

The way people often do them, they typically don’t. However, that can change if we rethink the purpose of the “social skills group” and where it fits within your service delivery plan.

Many social skills groups are delivered as if they’re the “complete package”. In other words, the student, or students, come in for therapy, do some role play or a lesson plan discussing feelings or social rules, and the intervention protocol ends there.

There might be an attempt at collaboration between professionals, but those collaborative efforts are thought of as the icing on the cake, not the cake itself.

When social skills groups are done that way, there is poor generalization (regardless of the credentials and skills of the person leading the intervention).

Sometimes kids may try to apply what they’ve learned to peer interactions, but it ends up feeling forced and awkward for them because they’ve learned a list of contrived rules instead of truly learning to read the room and respond during social interactions.

Many people draw the conclusion that we should ditch the idea of “social skills” or “social-emotional learning” completely, which is problematic.

It’s equally problematic to make the assumption that all social skills interventions are ableist. If you’re focusing on things like situational awareness and perspective taking, you’re teaching kids skills that are important for both neurotypical and neurodivergent people.

So…what is the “right” way to do social skills groups?

My first suggestion is to stop calling them “social skills groups”.

This could help reframe things for people and disrupt their default assumption of what happens in a “social skills group”.

Instead, we might just think of them as “meetings with students to prepare them for stuff coming up in their lives”.

In other words, there is an appropriate way for professionals to meet a student 1:1 or in groups to discuss upcoming events or situations; but the “meeting with students” is part of a bigger intervention plan, not the entire intervention.

It might still be listed as therapy minutes on their IEP, but we can think differently of how we utilize that time, and can potentially add some consultation minutes or accommodations to document other service models.

This goes back to the idea of “service delivery planning” vs. “therapy planning” because it requires multiple service delivery models.

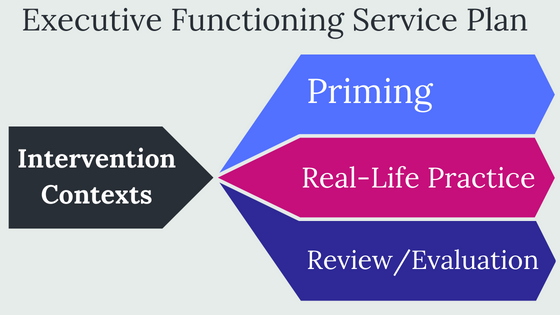

Social skills groups have three components when we think of them as part of a larger service plan: Priming, Real-life Practice, and Review/Evaluation.

Priming includes planning and preparing for upcoming situations to give kids strategies and cues. This can include role-playing, practicing skills in a structured environment, and front-loading information or strategizing to help kids envision and plan ahead for future events. Here is an appropriate place in the service plan to do “meetings with students”.

Real-life practice is where the majority of the learning happens. Adults supporting kids in their daily life should be prepared to model and scaffold so kids can apply strategies they’ve been practicing in therapy. In order to make this happen, you’ll need to utilize other models like consultation, coaching, supporting materials, and a bigger strategic plan. This is not something we can do in a “social skills group” format; it needs to happen in a naturally occurring context (including a combination of structured academic and unstructured social situations).

Review/evaluation is a part of intervention where adults can help kids reflect on past situations, evaluate their ability to apply strategies, and help make decisions about how to use that new knowledge for future events. Within the same conversation, you may cycle back to priming for the future as you fine-tune skills and fade prompts. Here’s another place it would be appropriate to do “meetings with students”.

We want to start with the service plan and THEN insert the student groups where they fit, instead of thinking of the entire intervention as starting and ending with the group.

Shift 3: Scalable Protocols vs. Lesson Plans

Once clinicians buy in to the idea of using multiple service delivery models and coaching others, they run into logistics issues. They say, “That sounds great, but how am I going to have time to meet with teachers?”

Others get stuck because even if they find time to meet with teachers, they don’t know what to do with that time.

This is because knowing how to deliver therapy yourself is a different skill set than knowing how to document your clinical protocols for purposes of training others.

Thinking of our session planning in terms of scalability is the first step in being able to train, coach, and supervise others.

Scalability refers to potential for growth and expansion. The easier a strategy is to define and document, the easier it is to scale. You can then “scale” it by training different people in the process so that it’s happening more frequently.

That’s why I make my protocols and materials as simple as possible in the School of Clinical Leadership.

Identifying your scalable protocols can give clarity on how to utilize professional collaboration time, because you’ve defined what information you need to share and where you might need to get feedback.

It’s often easier to scale operational things, like how to fill out payroll forms. With teaching and therapy where there’s a need for differentiated instruction, it gets much more difficult.

This is why school leaders focus so much time and effort on core curriculum. They face the challenge of implementing a curriculum that’s scalable across classrooms within grade levels, or when students move from one grade level to another.

The complexity of this task makes it difficult for school administrators to find the bandwidth to focus on adding additional layers to this process; such as universal support for executive functioning.

When therapists focus on scalability, this can look different. Here is where school therapists can become a huge asset by adding an additional layer of support on top of school administrators’ efforts.

This could mean that while you’re planning for therapy, you develop strategies that will be easy to document, share, and coach others to do.

“Scaling” for you could happen when you train other professionals in your building to do strategies in their classrooms. It could also include creating tools and resources that can be shared with caregivers.

A caveat here is that not every protocol can, and should be scalable to the point that people outside your discipline can do it.

There are some things that have to be delivered in a therapy session with a licensed clinician. This may mean you have a set of protocols that you intend to do yourself, in your sessions, but then you’d have other protocols that you’d intend to “scale” to other people.

With executive functioning intervention, we need to be even more intentional about making things scalable; or else we’re not likely to see good generalization.

That’s why in the School of Clinical Leadership, all of the strategies I teach are easy to scale because they’re incredibly simple and don’t require any special materials beyond normal day-to-day items (analog clocks, dry erase boards, calendars, images, etc.).

I provide a set of scalable protocols, but also give you the tools you need to create a strategic plan for putting other service delivery models in place.

The School of Clinical Leadership is a program for psychologists, social workers, speech pathologists, counselors, occupational therapists, or other service providers who want an evidence-based plan for supporting students socially, emotionally, and academically.

It only takes ONE team member to take the lead and get the team on track. That person can be YOU.

With the right system, it’s possible, even with limited time and resources, and even if you’re not in an “official” leadership position.

The School of Clinical Leadership gives you the tools and systems you need to design services that build resilience and independence.

But it doesn’t stop there.

I’ll also help you develop the systems and operating procedures needed to make it a reality.

You can learn more about how to become a member here.