Why isn’t there a language therapy curriculum?

When I ask SLPs what would help them feel more confident, a lot of times they say that they wish there was a standard “curriculum” they could use for language therapy.

When I was first practicing as an SLP, I wished for something like this. I was jumping around from skill to skill, never feeling like I was making consistent progress with my students. Materials I’d purchased were collecting dust on my shelves, and I spent way more time than I’d like to admit searching the internet and putting together craft activities that totally bombed and ended up distracting students.

In short, I was putting in a lot of effort but never seeing the fruits of my labor. It made me doubt myself as a therapist and wonder if I was really making a difference. I felt like a fraud, because I’d assumed that by the time I was out in the field, I’d know what I was doing. But I didn’t feel that way at all.

That’s why when I went back and got my doctorate in special education, I decided to specialize in language and literacy.

I searched for a “curriculum” for language therapy…or at least some standard protocol that would feel comprehensive enough for my caseload.

But I never found one.

That’s why I decided to create my own system for language therapy during my doctoral work.

As was doing my research, I tried pieces of the framework with my own caseload; and over time I developed a system that allowed me to help my students meet goals consistently (without spending hours laminating).

This process is what helped me go from hating language therapy to actually looking forward to my sessions…

It’s also what helped me finally get respect from my colleagues and walk into IEP meetings confident and excited to share my progress updates.

I’m going to outline that system for you today, but first I need to answer a couple looming questions.

Mainly…why was a system like this so hard to find in the first place?

It comes down to a couple key reasons that I’ll break down one at a time.

- Confusion about school-age language developmental milestones

- Treating the symptom and not the cause.

- Lack of clarity about the SLP’s role.

Confusion about school-age language developmental milestones

If you’ve ever done a search for developmental milestones for language, you’ll likely find lots of great infographics and handouts that explain early language development. The problem is that most of them stop around age 6.

For those of us trying to make sense of what to do with school-age kids, that presents a problem; mainly that it’s hard to diagnose and treat something if you don’t know what is “normal” or “typical” (I use both of those terms loosely).

Either way, SLPs need some kind of a benchmark or guidelines in order to be able to determine if a disorder is present. Sure, we have lots of norm-referenced assessments, but you likely already know that a lot of them have biases or limitations to the information they provide.

That means we need to do additional, non-standardized procedures and observations to help with diagnosis and treatment planning.

So…why aren’t there any resources with school-age language milestones floating around out there?

Mostly because those neatly-defined milestones for school-age don’t exist. At least not the way you’d expect.

I think that Loban (1976) put it best in his seminal article about K-12 language development when he said:

“Drawing up a valid chart of sequence and stages is hazardous; at any one age children vary tremendously in language ability.” (pp. 93)

The reason that this is the case is that language growth across the school-age years isn’t linear. Most of them don’t increase in a neat, upward linear progression.

The other thing to remember is important language skills, like vocabulary, are highly dependent on environment.

That’s why instead of asking the question, “What words are age-appropriate for X grade level?”, we should be asking, “What words are kids being exposed to at X grade?”.

Of course, the answer is going to vary for each kid! Again, this is why we can’t put things in a neat little “curriculum” box.

What we DO know is that there are certain set of skills that kids need in order to develop the high-level processing skills needed to be successful in school. That’s where the framework comes in.

In order to understand that framework and how to use it, we have to understand how to funnel down the massive list of language skills we COULD be working on to manageable amount.

That brings me to my next point.

Treating the symptom and not the cause

I get a lot of questions about things like reading comprehension strategies, stating the main idea, inferences, narratives, and how to do “literacy-based” therapy.

All of these things have value, but they are often done out of sequence.

Without the foundational language skills needed to understand words and sentences, high-level comprehension will suffer.

If kids don’t have a solid sense of vocabulary and sentence structure they aren’t likely to complete high-level comprehension tasks focused on getting the “gist” of what they’ve read and heard (Scott, 2009; Nippold, 2017). That’s why people often feel stuck when working on goals like following directions or “wh” questions about inferences.

Kids often don’t have the language skills needed to focus on the “big picture” of what they’re reading or hearing. .

Struggling with comprehension is often the SYMPTOM of underlying language issues at the word and sentence level.

This was a big “aha” moment for me as an SLP because I was constantly scrambling to work on a million different language skills. I didn’t realize that there’s a “domino” effect with certain language skills; in other words working on word and sentence-level comprehension can have an impact on high-level comprehension.

One common mistake people make is focusing on the harder skills (like comprehension and inferencing) and neglecting the foundational skills (like vocabulary and sentence structure). This can leave kids feeling frustrated.

Imagine if you had a hard time with something, and you went to get help. But when you got there, the person helping you just asked you over and over again to do something you didn’t know how to do.

Asking certain kids to do comprehension tasks can be like throwing them off the deep end without teaching them how to swim.

Swimming in the deep end might be the end goal. It might make sense to practice it at some point. But not yet.

Some people go to far in the other direction and focus on skills that aren’t very functional when done out of context. An example would be things like verb tenses, or categorization. All of those things have a place in language therapy, but only when addressed in the right situation.

The most common scenario is that people bounce back and forth between skills that are too hard and skills that are decontextualized without a system to bridge the gap in between. This results in a long laundry list of skills that SLPs feel they have to cover; which leaves them scrambling and jumping around from skill to skill with no rhyme or reason. If you’re treating school-aged kids, you know what I mean.

The list of language skills can look like this:

Main idea, Inferences, Narratives, Sequencing, Categorization, Associations, Pronouns, Verb Tenses, Following Directions, Subject/verb agreement, Vague “processing” goals, “Wh” questions , Multiple meaning words, Plurals, Possessives, Basic concepts, Antonyms/Synonyms

This is just the beginning, but as this list adds up over time, it can start to feel disjointed. It doesn’t help that there are a million language activities, games, and apps you can choose from and a ton of research to sift through.

The truth is, there are some things on this list that aren’t a high priority to target. Others may be relevant to target EVENTUALLY, but might not be an immediate priority.

We often end up treating the symptom and not the cause because we’re simply overloaded with information and don’t know how to sequence our strategies properly. So many professional development seminars are hard to apply to real-life situations, so it leaves SLPs in a tricky position.

That’s why if you’ve done any of the above that I’ve mentioned, it’s not your fault. I used to do the same thing due to information overload.

That all can change for you if you follow the right system.

But before we can talk about that, we need to understand why the idea of a “curriculum” doesn’t make sense for SLPs in the first place.

Lack of clarity about the SLP’s role

I get why people want something scripted and specific they can follow. On the surface, it seems like it could make life a whole lot easier. But that might not necessarily be the case.

Curriculums may work fine for teachers because it’s their job to deliver the curriculum. They are experts in knowing grade level expectations. But you, as the SLP, are NOT a teacher. You are a therapist, and therapy is individualized. That means that one size doesn’t fit all.

The problem with a curriculum is that no one cookie-cutter play-by-play is going to work for your caseload. But you already know that.

Therapy is supposed to be individualized. But starting from scratch with each case can mean a lot of work for YOU as the SLP when you have a caseload of 40, 60, 80, 100 (or some other ridiculous number). If you work with pediatric populations, a good portion of your caseload is likely language cases.

If planning for language therapy is sucking up a lot of your time, that can get really stressful very quickly. So while SLPs can’t have a “curriculum”, we can develop something ELSE that is “just right” (kind of like what Goldilocks was going for).

We need something that is flexible enough that it meets your students’ unique needs…but structured enough that you’re not starting from scratch each time you get a new language therapy referral. I refer to it as a “framework”.

You also need a starting point that allows you to identify the key areas where you need to focus in order to build the academic language skills students need for high-level language processing.

And then within those areas, a set of strategies you can cycle through; that are easy to customize and scaffold for different ages and ability levels.

That’s exactly what this system does.

The Language Therapy System

While the idea of a “curriculum” doesn’t quite fit for an SLP’s role, we can have something better that’s a better fit for our students.

I like to refer to it as a “framework” because it’s flexible enough to account for your students’ individual differences but systematic enough that it’s consistent, effective, and efficient.

I started to develop this framework in the beginning of my doctoral work because I was frustrated with my lack of a good system for language therapy. I was tired of spending so much time planning and feeling like my students never made consistent progress.

The burnout was getting to me, and I knew something had to change.

Within the first few years of working in the school systems, I joined the building problem-solving team in my district.

The purpose of this team was to field all the referrals for academic and behavioral concerns; and it consisted of a combination of different teachers from general and special education, a building administrator, the psychologist, the social worker, and the speech-language pathologist.

As I sat in on these team meetings, I noticed that most of the students referred for evaluations for academic issues had issues with vocabulary; based on teacher reports and often based on my language evaluations.

At the time I was doing a lot of research on Response to Intervention, literacy, and language in my doctoral program; and a lot of the literature I was reading pointed in the same direction.

That’s when I knew I was finally getting closer to finding that “language therapy system” I’d been looking for.

What I found when I dug in to the research was that vocabulary skills were correlated with a lot of the “big picture” academic and language skills I’d been working on with my students (Dudek, 2014).

Things like reading comprehension, being able to make inferences, or being able to retell information they’d read. Even being able to compose written assignments with detailed, organized sentences. Vocabulary impacted all of them.

When it came to reading comprehension, I found that you need to know 90-95% of the words in a text in order to comprehend it (Schmitt, Jiang, Grabe, 2011). If you don’t have that background knowledge of the words in a text, you’re going to miss the overall message because you get too bogged down with trying to make sense of what the words mean.

This sounded like the EXACT scenario that teachers in my building would describe when making referrals to the team.

“When I ask him questions about what he just read, he just gives me a blank stare.”

“We spent 30 minutes talking about the ‘Ghost in the attic’ story. Afterwards I realized she was lost the whole time because she didn’t know what an attic is!”

“Sometimes she has a hard time coming up with the right word when she’s explaining things to me. Even words that I think most kids should know at this age.”

All of this led me to create a system for language therapy focused on ONE key area addressed systematically (instead of a bunch of random skills thrown together out of sequence).

It’s what helped me get my students to their LREs consistently (and in some cases, out of special education completely.).

It’s what finally made me feel like a language expert instead of a glorified teaching assistant or the “speech teacher”.

It’s also what made me go from hating language therapy to making it my life’s work.

I created that system using a framework I refer to as the “essential 5”.

To understand the “how” and the “why” of the essential 5, we need to talk about where vocabulary fits in to the picture.

I used to think that vocabulary was just about knowing definitions of words; or being able to label and identify words. That’s why I also didn’t realize that focusing on this ONE area can have a global impact across the board on how kids function in school.

But when we address vocabulary in a way that targets these 5 components, it can serve as a foundation for your therapy.

Vocabulary skills are what I like to refer to as “the first domino”. In other words, targeting this ONE area in the right way can have a domino effect on everything else you target further down the line.

This is “domino effect” is critical because you only have a limited time with your students. You have to make every second count and pick strategies that have a maximum impact.

You want to think of more challenging skills, like inferencing and high-level comprehension, as the other dominos further down the line.

Why start at the back of the line and knock each domino down individually when you can just focus on knocking down the first one?

When we “knock down” the first domino (vocabulary), we make it MUCH easier for the other dominos to fall. It doesn’t mean we don’t ever address them. We just don’t want to address ALL the skills at once.

Addressing vocabulary helps to give our students the underlying language skills they need for high-level comprehension. Some kids will improve their overall processing skills without ever needing direct comprehension work from you in language therapy. Others might need this work eventually; but if you build a strong foundation, they’ll actually be able to respond to that type of work.

The way we actually make those dominos fall down and improve vocabulary is that we need to develop a repertoire of strategies we can use to address all the skills that contribute to vocabulary knowledge. Then, once we’ve developed those protocols and established a set of simple materials we can use while implementing them, all we need to do is consistently cycle through them.

This is what eliminates the overwhelm for YOU, and at the same time focuses only on the skills students need in order to make consistent progress (instead of jumping around from skill to skill without making progress on any of them).

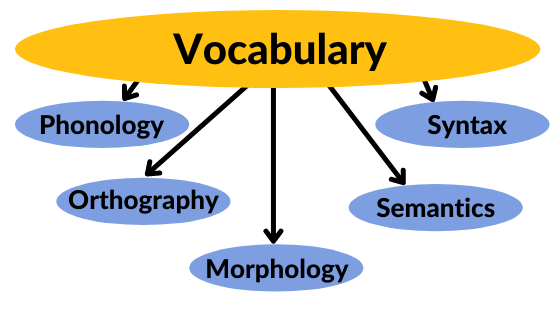

In order to target vocabulary in a way that boosts overall language processing, we need our treatment strategies to facilitate growth in the following areas (Kucan, 2012):

- Phonology

- Orthography

- Morphology

- Semantics

- Syntax

Vocabulary is like a broad umbrella, with 5 areas that fit underneath it. These 5 components all contribute to our vocabulary knowledge. They are all interrelated with overall vocabulary growth; as well as each other.

Component 1: Phonology

The first linguistic component that impacts vocabulary is phonology, the study of a language’s sound system. A lot of times we think of phonology under the realm of speech sound disorders, like having a disordered sound system and not pronouncing the words the right way; but we won’t use a word often and effectively if we can’t say it. Part of knowing a word is having a good “phonological representation” of a word (Sutherland, 2009).

Part of our concept of a word comes from hearing all of the sounds in the word together in sequence, recognizing them, and putting meaning behind what they all mean collectively together. When you put all those sounds together and grasp the meaning of the word, that’s what happens when that phonological representation develops.

Because our ability to use words depends on our phonological representation, we’ve got to make sure that we integrate a phonological component within the way that we work on vocabulary.

Component 2: Orthography

The second linguistic component in the “essential 5” is orthography, the study of a language’s spelling system. Orthographic knowledge is the awareness of how a word looks in print and the meaning behind how a word is spelled (Kucan, 2012). If you have a weak orthographic representation of a word, that’s going to impact how efficient you are when you’re decoding.

The ways words are spelled can also give key information to their meanings (like homophones and homonyms). In addition, there are also individual word parts that give us clues as well about the overall word meaning (like prefixes and suffixes), which has to do with morphology, our next component (Kiefer & Lesaux, 2007).

Part word retrieval and recognition is being able to look at a word and recognize it automatically. When you’re able to do that quickly and draw all of those associations, you have what’s called a “mental orthographic image” (Apel, 2009). This is why integrating strategies that build these skills are so important in our vocabulary interventions.

Component 3: Morphology

The third linguistic component in the “essential 5” is morphology, the study of forms of words. The morphemes in the word will impact how a word is spelled. When we’re talking about morphology, we’re talking about the study of word parts, like prefixes, suffixes, roots, bases, and grammatical markers (Apel & Lawrence, 2011).

All of these individual parts having meanings, and they also impact the overall word’s meaning. This means that if we change word parts, like a suffix, for example, we might change the meaning or class of the word. Or as another example, if we put a grammatical marker on the word, part of the word would remain the same, but we’d be getting information from that grammatical marker.

This is also why it’s important to target morphology.

Component 4: Semantics

Linguistic component number four is semantics, which is what a lot of us think of when we think of vocabulary. Semantics refers to meaning and the pieces of information associated with the word. Semantic features are different attributes that give us information about what words mean (Dudek, 2014). For example, with the word “cat”, we might think of the category, of “animal”. We might think of physical attributes, like the fact that it’s furry. Or we might think of functions or things a cat might do, like make a meowing sound.

If we’re studying things like verbs and adjectives the semantic features talking about synonyms, antonyms, associations. For our students with language disorders, they don’t store semantic information as efficiently and as automatically as other students.

They need us to be a lot more direct and explicit with them in addressing things like semantics. This is why the standard instruction in the classroom is not enough for them. We need to take it a step deeper and be more direct with teaching this semantic information compared to what other kids might need.

Component 5: Syntax

The fifth linguistic component is syntax, the study of sentence structure. We’re not going to develop deep knowledge of words if we don’t use them consistently, and having a solid sense of sentence structure can help us do that (Kucan, 2012).

Vocabulary isn’t just about what words mean; it’s also about what words do.

Knowledge of content words in a sentence is not enough. We also need to know the function of different sentence parts, as well as the function words in the sentences. This might include words like prepositions or conjunctions. Without understanding what those words are doing there and what they’re telling us, comprehension is going to suffer. Function words are like the glue that holds the content words together, and that’s why it fits in with vocabulary.

It’s important to note that one of the most important skills that can have an impact on overall comprehension is a student’s ability to comprehend complex sentences. This is a skill that’s highly dependent on one’s ability to be aware of syntactic cues and how each word in the sentence is functioning (Loban, 1976, Zipoli, 2017).

We need these skills to be intact if we’re going to understand the overall message. This is why kids aren’t likely to respond to strategies focused on high-level comprehension if they can’t comprehend individual sentences.

How to create your own language therapy system

Now that we have all the pieces, we can start putting them together to create that domino effect.

The next step is to start developing a set of protocols that hit all of these 5 components based on the research; which is exactly what I teach people to do in Language Therapy Advance Foundations.

On a high level, the strategies you’d want to use focus on word study. Sometimes you might want to be studying meanings of words in a way that teaches kids both a strategy for self-questioning and word-retrieval like this. We also want to teach kids the syntax of word definitions because as I explain here, this is one skill that can impact academic performance.

You’ll want to address specific syntactic structures that are known to have an impact on reading comprehension and written language performance such as these.

And of course, you want to have a sequence for doing these things so you can have an efficient system that reduces burnout for YOU, and decreases confusion for your students; which is what I walk you through in Language Therapy Advance Foundations.

At this point, I want to answer some of the common questions that come up for people as they’re learning how to implement this framework.

Frequently asked questions about the 5 component framework

At this point, most people are excited about the idea of a comprehensive system that can help their students get consistent results in therapy; however, many people have some clarifying questions to help them ensure that this is a good fit for your students. That’s why now I’m going to share some common questions I get about this “essential 5” framework to remediating language processing issues.

What populations can benefit from this framework?

What I’m going to do here is go through some common populations people ask me about when I explain this framework. I also periodically mention my course, Language Therapy Advance Foundations because I show you how to implement the process in that program.

Central Auditory Processing Disorder

Underlying language issues at the word and sentence level can cause issues with high-level processing, which often present as “auditory processing” issues. There’s also evidence that addressing those issues with vocabulary/sentence structure will improve processing, while there’s not a ton of evidence that you will create functional gains with drill-type activities aiming at increasing working memory-so I don’t recommend spending a ton of time on those types of things. The skills we’re working on while addressing essential 5, on the other hand, result in better transfer of skills to real-life tasks.

I focus on teaching what we know works; especially because there’s also been research to show that many children won’t respond to instruction focused on high-level comprehension if we don’t address those foundational deficits. What we’ve found is that when you address those underlying issues, the overall language processing abilities improve.

English Language Learners/Bilingual/English as a Second Language

I have mentioned a handful of SLPs who use this system to work with students who speak English as a second language. Our framework doesn’t cover a specific, separate protocol for this population, but rather focuses on teaching strategies designed for individuals with language processing issues.

SLPs who have come in before have found it easy to implement for that particular population, because it really focuses on building metalinguistic awareness skills and word study skills; which is really important for people learning a new language AND also students who struggle with language processing overall. However, it’s important to note, all our materials and strategies are in English and designed to improve functioning in that language.

Specific learning disabilities (dyslexia, dysgraphia, etc).

This framework will help students with dyslexia and dysgraphia. Since we know those disorders are language-based, addressing underlying language issues at the word and sentence level and focusing on metacognitive skills can make a huge difference for them. Also, we will show you how to focus on morphology, orthography, and phonology-which is critical for those populations.

What we’ve found is that a lot of programs out there will show you frameworks for working on those skills, but not in a way that’s feasible for SLPs with only one or two sessions per week (a lot of programs are more for teachers and reading specialists who have daily sessions). However the “essential 5” framework will help you address those skills in a way that’s manageable with a typical SLP schedule.

Autism/ADHD (pragmatics and executive functioning)

If you have a student who needs to work on vocabulary and comprehension and who also has ADHD or autism, this process will help to address those issues. While the framework does not address pragmatic language specifically, becoming more aware of how you use language can have some carryover effects and make people more aware of the perspectives of other people. However, since we don’t address nonverbal communication and social skills directly, there might be some other strategies you might need to teach students with autism or ADHD.

The same thing applies for executive functioning; building language processing skills can reduce the cognitive load; which can often make it easier to attend to tasks. Attending issues can become worse if you layer language processing difficulties on top of it. Reading comprehension, writing, and many other functional day-to-day activities require executive functioning skills. However, we need to have the underlying language skills to support those skills; which is why this framework can support those other skills. There are definitely some students who DO need direct work on those high-level skills once they’ve established a foundation; but they will respond more favorably when you address some of the processing issues.

Low IQ, moderate to severe language delays

The essential 5 framework is focused on building academic language skills needed for language processing and literacy skills like reading and writing. It is a good fit for individuals in the mild to moderate range, who are anticipated to have a decent amount of access to the general education curriculum, and who will be expected to be on an academic track through school rather than a functional/life skills track. It’s not a fit for individuals who are minimally verbal and who are using AAC.

If you have students who are in a life skills curriculum or who have cognitive delays, and they are in early elementary school, it’s possible that they may still benefit from this process because at that age, cognitive skills are still developing. I tend to err on the side of exposing kids to the materials and having higher expectations rather than assuming that they won’t be able to learn the information. So if you have students who have moderate language issues and you aren’t sure if they are high functioning enough to benefit, I would still recommend trying the framework with them

What age groups can benefit from the essential 5 framework?

I have SLPs who use this framework we teach for students ranging from Kindergarten all the way through high school. I also have a fair amount of SLPs who work solely with students in junior high and high school and they’ve found it a great fit for their students. If you have students who are very young, preschool and younger, it won’t be a good fit for you.

This is a framework for building metalinguistic awareness and word study. In Language Therapy Advance Foundations, I teach a set of strategies that you can use with students all the way from K through 12. You can simply modify the content you’re using (so typically, the vocabulary you’re studying) to make it more or less difficult using the same set of strategies. This way, you can tailor it to your students’ unique needs and what’s specifically being covered in their curriculum, and still stick with the same core strategies and framework; which ensures that you and your students get very proficient with those core techniques.

Since grade level curricular materials and what’s age-appropriate for a given age is so dependent on exposure and environment, as well as geographical region; it would be hard to come up with one set of curricular materials that would work for every single situation (which isn’t really what you’d need anyways). Remember as I talked about earlier; the reason it’s hard to find a structured “hierarchy” that specifies exactly what skills need to be taught at what age is because language growth is not linear. Coming up with a framework that rigidly divides things up by age and grade level would be counterproductive.

What you want to do instead is have a process that you can customize based on your local curriculum and the needs of your students. You also want something that you can easily replicate with simple materials and activities-which is what the essential 5 framework helps you do. I show you how to do this; plus share worksheets and materials you can use to do this in Language Therapy Advance Foundations.

How do I handle evaluations and writing goals with this framework?

Since the techniques I teach you are simply a different strategy to achieve the same end goal that you’re probably already working towards (e.g., better processing skills/better comprehension/better academic performance), there’s no need to re-write any language therapy goals before implementing the strategies in the program-you can simply start doing them and tweak your language goals over time as IEPs and evaluations come due.

In Language Therapy Advance Foundations, I provide you with a manual called the SPOT framework guide where I walk you through how to write goals, how to collect data and track progress, and how to use various data sources to make decisions (like classroom assessments, work samples, standardized language assessments). I show you how to gather information from the information you have rather than requiring you to start from scratch and have to re-evaluate each student.

Does the framework address verb tenses, parts of speech, pronouns, antonyms/synonyms, and categorization?

When you use the essential 5 framework, you’ll focus on the highest priority skills that have the biggest impact on overall language processing. The truth is, not all language skills need to be targeted directly or deserve to have a goal devoted to them. This is a good thing-because you wouldn’t have time to address all of these things anyways!

Working on pronouns doesn’t have a huge impact on comprehension and overall expression, so I don’t recommend targeting pronouns as an attempt to improve language processing. I know there are other conversations to have here, such as the clarifying pronouns people use to address themselves; but pronouns goals don’t need to be on a language IEP.

Instead, we want to focus on high priority skills, such as those that enable people to expand their use of different sentence types. Doing this has an impact on overall comprehension, which increases the chance that they’ll be able to read complex texts or compose longer, written essays. Both of these things will give kids more experience using language, which increases language growth over time.

Other skills like antonyms/synonyms, parts of speech, categorization, and verb tenses are relevant to target when done in the RIGHT CONTEXT. I show you how to do that in Language Therapy Advance Foundations.

How does this framework compare to strategies in other literacy programs or memberships for SLPs?

A lot of other programs and materials out there for SLPs provide strategies for discrete language skills. For example, you’ll find a lot of worksheets and flashcards focused on things like categories, verb tenses, or even “wh” questions. There are even some that focus on thematic units and vocabulary. All of these things are fine; but SLPs often experience information overload. There are so many different options as far as materials and activities that figuring out how to sequence them together into a good system takes a lot of time.

I experienced this frustration first hand when I first started as an SLP. The “essential 5” framework, on the other hand, does not require you to sift through a ton of different materials and activities. Instead, it helps you laser-focus on just a few simple techniques-which minimizes the time it takes you to plan your sessions. You can implement it effectively with just a dry erase board, markers, and some simple word lists once you get good at utilizing the core strategies.

The main difference in this framework is that it is a system instead of discrete strategies. There’s nothing wrong with a lot of the other resources out there as long as they’re sequenced in the right way (and as long as you don’t spread yourself too thin trying too many things).

When it comes to some of the literacy curriculums out there (like Wilson, Orton-Gillingham, etc.) the “essential 5” would definitely fall in line with some of the principles in that program. Using it in conjunction with one of those other programs would be complementary; but the essential 5 is is not the same as a lot of literacy programs because covers how to do word study from the SLP’s perspective (incorporating phonology, orthography, morphology, semantics, and syntax).

A lot of programs are more geared towards teachers/reading specialists who have sessions every day with kids, while a lot of SLPs might only see their students once a week, which makes them hard for SLPs to implement. On the other hand, the essential 5 framework is feasible for SLPS even with 1 session per week (and you can customize it for more frequent sessions as well).

How do I learn more about how to implement the “essential 5” framework?

If you haven’t guessed already, the “next step” for you if you want to learn how to build your students’ vocabulary and processing skills is to join us in Language Therapy Advance Foundations!

Language Therapy Advance Foundations is a self-led online course specifically for SLPs who work with K-12 students that struggle with reading comprehension and language processing difficulties.

Over the past few years, we’ve helped hundreds of SLPs transform their language therapy practice and make breakthroughs with their students. You can learn how to become one of them here.

The program consists of 6 training modules that walk you through your new “scope and sequence” for helping your students consistently achieve their therapy goals. You’ll learn things like:

- How to build deep semantic skills that increase word storage and retrieval.

- How to use definition syntax that improve retention and use of vocabulary across settings.

- How to build syntax skills that support comprehension and written expression across contexts.

- How to build spelling, decoding and language skills through targeted word study.

- How to keep language therapy structured, intensive, and efficient to support generalization.

You can learn more about what’s included and how to become a member here.

References

Sutherland, D. (2009). Phonological representations, phonological awareness, and print decoding ability in children with moderate to severe speech impairment. (Doctoral thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand) Retrieved from: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/1292/thesis_fulltextpdf;sequence=1